To the TIDE Blog...

Aug 14 2017

The Limits of Restoration? Legacies of the Seventeenth Century in the Anglo-American Built Environment

John Ward House, begun in 1684, and restored/moved in the early twentieth century.

Early modern individuals frequently expressed the inevitability of physical decay. ‘The World it Selfe is dying and decaying’, wrote the poet Josuah Sylvester in the 1610s. ‘In all This World, All’s fickle: nought is Firm’. In many ways, it is remarkable that anything from the seventeenth century survives at all. Centuries later, the studs, posts, frames, and bricks from many early colonial houses quietly, if precariously, endure. Doors, staircases, chimneys, and makers’ marks etched on beams evoke, and often allow us to step into, a four-hundred-year-old past.

A recent trip to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire piqued my interest in some of the questions around restoration and preservation. Since the best way to reach Dartmouth requires taking a coach from Boston, I had the opportunity to visit several historic sites in New England. Some of the earliest surviving timber-frame houses in North America are in Massachusetts, built in the recognizably post-medieval style of late Tudor and Jacobean England. The historic landmarks in the coastal city of Salem, officially incorporated in 1629, expose some of the complexities inherent in heritage preservation, raising issues of both tangible and intangible heritage and revealing ongoing debates about early colonial identity, English and American history, and heritage management.

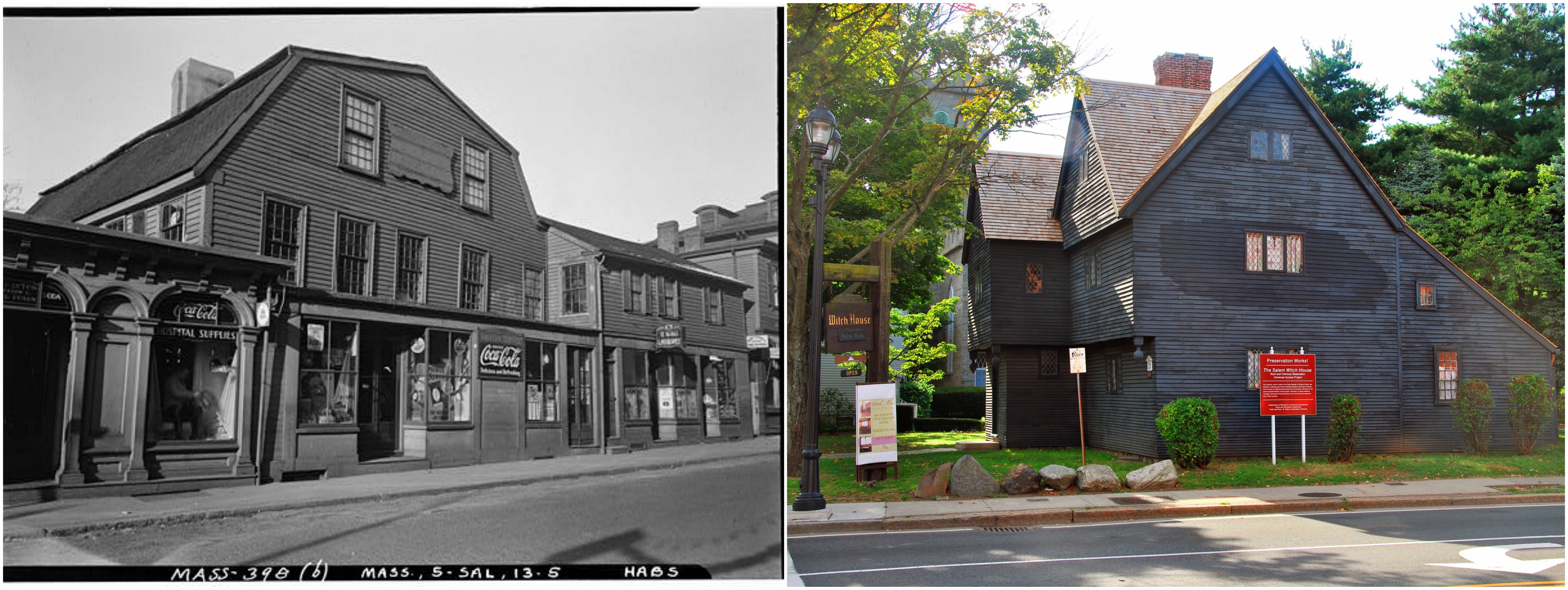

The seventeenth-century ‘Witch House’, once belonging to the witch trial judge Jonathan Corwin, has the timber framing, chimney, and gabled roof that at first glance suggests it to be a ‘typical’ early colonial structure. Recent visitors to the house posted reviews on Trip Advisor that maintain, as do reports in the Library of Congress archives, that the house authentically dates to the mid-to-late seventeenth century, and provided the locus where the witch trials were partially conducted. Yet no documentary evidence suggests that any proceedings occurred there, and images of the Corwin house in the 1930s show a very different structure, one that has been inhabited and remodelled extensively over the course of its history (see image below). Restoration work in the 1940s therefore required a committed large-scale project that involved moving the house 35 feet to its current location, altering internal and external features including the roof and windows, and painting the wooden facade black to resemble the ageing effect of timber, casting a mood that well suits the house’s sombre evocation of the trials.

The Witch House as it stood on Essex Street at the time of the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) report, c. 1933; the Witch House as it now stands.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the act of restoring as ‘to return a thing to a former state or position…[t]he action of bringing back into existence; re-establishment, reinstitution.’ To bring back, however, is not quite the same as preserving or conserving: can a four-hundred-year-old house be ‘brought back’ into existence after it is gone, and if so, whose or what purpose does it serve? The Corwin house has been an important part of Salem’s gradual move, in the later twentieth century, towards embracing its dark heritage and encouraging a local tourism industry. The playwright Arthur Miller, visiting the city in the 1950s to write The Crucible, noted a disconcerting silence regarding the history of the 1692-3 witch trials. Bolstered by the filming of the sitcom Bewitched in the 1970s, the stories of the twenty executed individuals, and the two hundred others accused of witchcraft, are now an integral part of the town’s touristic appeal. Heritage and tourism overlap, but do not align completely. The cultural landscape now evokes the rise of seafaring mercantilism and the authority of a fledgling puritan presence in America alongside modern celebrations of the spectral. The latter greatly differs from the climate of social malaise and spiritual uncertainty that fuelled the historical witch trials, and the Corwin house sits at the crux of these pressures. How much can, or should, a house be altered to produce an entity that now looks seventeenth-century – and in some parts still is – while conforming to contemporary notions of what an early New English home should look like? Regional identity becomes tied to public perceptions of what the past is, what it looks like, and how relevant or applicable it is to the contemporary.

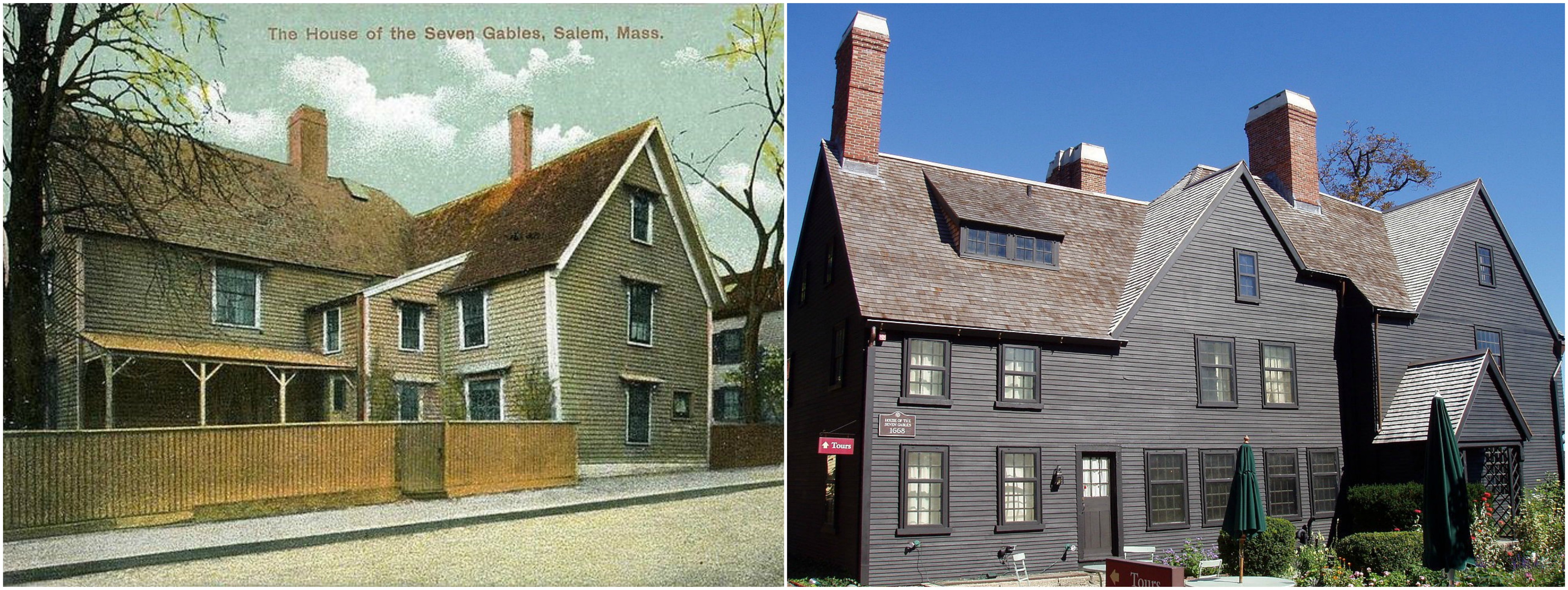

The House of the Seven Gables, also in Salem, has its own visitors’ expectations to contend with. It is widely assumed to be the inspiration for the author Nathaniel Hawthorne’s novel, The House of the Seven Gables (1851). Hawthorne’s works, with their mix of puritanism and nineteenth-century romanticism, evoke the radical Protestant reformer Martin Luther, the 1615 Overbury scandal at the Jacobean court, and the ‘apostle to the Indians’ John Eliot, who translated the bible into Algonquian and dedicated it to Charles II. Hawthorne even named his first daughter Una, after the Elizabethan Protestant epic, The Faerie Queene. In the words of the National Parks Services report, the House of the Seven Gables contains ‘layers of architectural significance’ ranging across four centuries. John Turner, for whom the house was built in 1668, had grown prosperous enough to commission additions within years of building the house, in a process of renovation and extension that continued into the eighteenth century. In a remarkable example of art transforming life, the house underwent further changes in the twentieth century, with new gables (‘the vertical triangular piece of wall at the end of a ridged roof’, OED) included to make seven, and where an ersatz shopfront was added to resemble the one used by a fictional character. The museum at the House of the Seven Gables is forthright about the structure’s elements of restoration. Architectural models contain puzzle-like pieces that show the layers of renovation over time, and the tours point out the original elements of the structure, while also noting Georgian additions like sash windows and turquoise wood panelling.

House of the Seven Gables, c. 1905, photo courtesy of WikiCommons, juxtaposed against the restored

building today.

Finally, as a contrast, I was charmed but somewhat disoriented when I encountered the Stuart-style mansion of Castle Hill. Its features reflect the tastes and fashions of many of the later Stuart elite – landscape gardens, classical-style avenues, bathhouses, an abundance of brick and stonework, and carvings imported from England. Though the site had been marked out as a place of settlement by colonists from the early seventeenth century, the house was built in the 1910s and 1920s. It is a remarkable instance of golden age luxury and early modern grandeur. Yet the estate, even when meticulously conforming to early modern architectural principles, looks like the fantasy home it was created to be. It is the simple, at times seemingly rustic architecture, expanded and fashionably furnished to reflect the rise of mercantile advancement as a result of its coastal topography, that remains at the heart of eastern American notions of its foundations. In its opulence, Stuart neoclassicism seems out of place.

Castle Hill, completed in the 1920s, built in the style of a Stuart estate.

Historic architecture in New England reveals the lasting influence of early modern transculturality, and offers a case study into how mobility and settlement – as well as ideas of home – profoundly influence the character and culture of geographical spaces. Early modern architecture, like objects and texts, begin to appear as active agents in shaping individuals and national stories, though their survival shouldn’t be taken for granted: these are the result of decades, centuries, of human maintenance and care. The House of the Seven Gables also testifies to the power of storytelling and regional memory in how individuals engage with and interpret the past. Hawthorne added a ‘w’ to his surname to disassociate himself from the merchant and magistrate John Hathorne, an ancestor who remained unrepentant about his role in condemning women in the witch trials. The houses discussed here raise a series of related questions: what should we commemorate or remember? Is it right to modify a building to restore it, even if little of the original remains? How can heritage sites attain levels of transparency and authenticity while still drawing visitors, a pressure that is applied by local and national institutions including, increasingly, city planners and government agents? What is the best practise for adapting and preserving historic buildings in ways that speak to current and future needs? How is the ‘essence’ or historical character of a building actually maintained? How, in the words of James Marston Finch, do we balance public and private pressures and manage the built world we inhabit? In a world of copies and digital representations, of pastiche and mass production, the real thing matters.

Lauren Working