The romantic, widely-marketed image of Venus and her luscious island of love casts a respectable veil over the sex and sacrificial killing of ancient myth, orgiastic rites that early modern writers gleefully explored. But, in the later colonial period, there was a more nefarious return to those early modern perceptions of violent, excessive indulgence. Ancient and early modern myths matter, and persisted, in the making and unmaking of modern Cyprus.

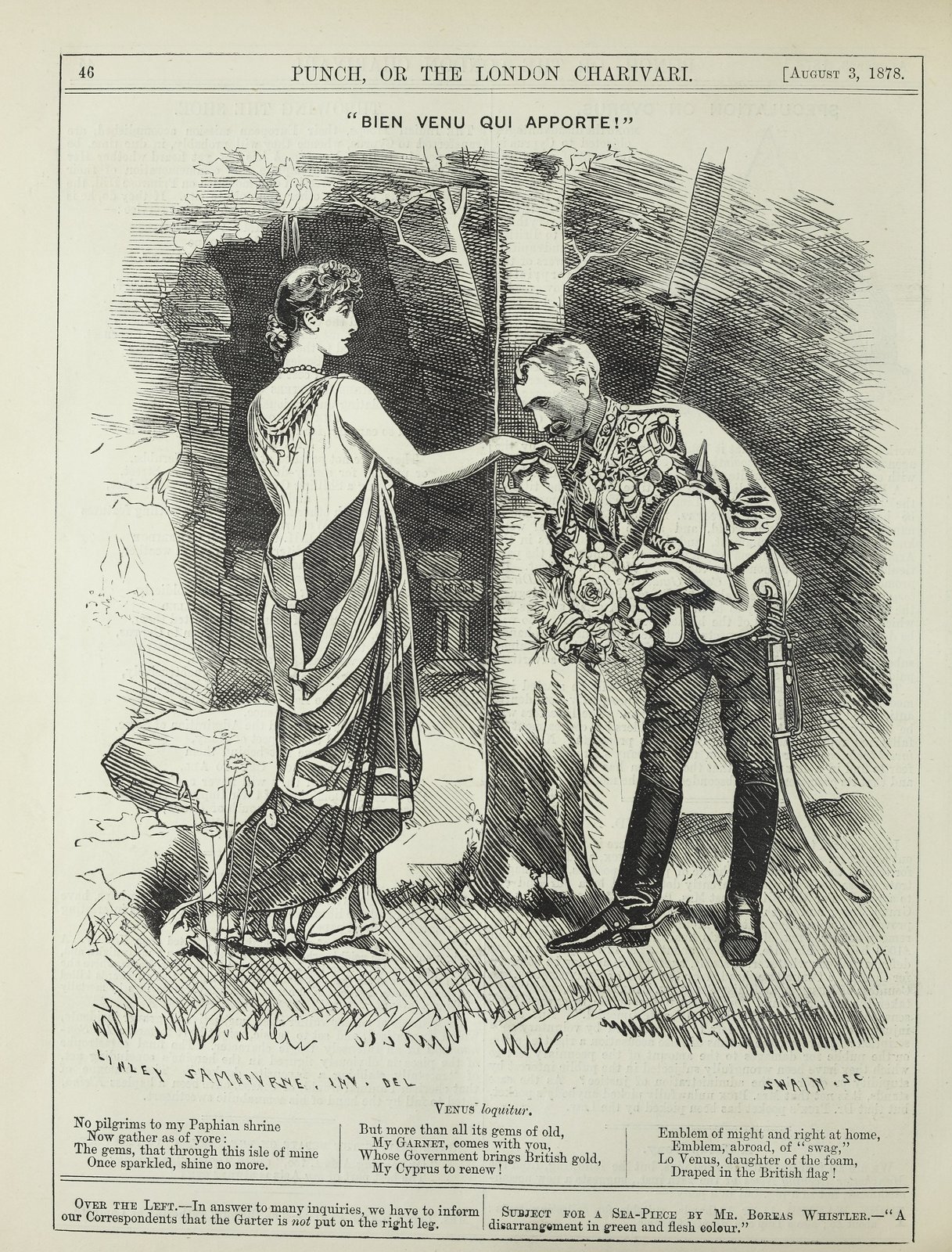

When all was well with British rule in Cyprus, Venus was depicted as a friendly and pliant goddess. Punch magazine had her draped in the Union Jack to welcome Sir Garnet Wolseley, the island’s first High Commissioner. This very Victorian goddess – whitened and receptive – is the one most recognisable to us today. But she signified more than love, romance and meaningful gazes: Venus and her people were portrayed as willing subjects of domination. Sir Richmond Palmer, governor of Cyprus in the 1930s, made it clear when explaining that both Cypriots and their goddess ‘expect to be ruled, and, in fact, prefer it’ (quoted in Given: 423). In other words, Palmer expressed that Cypriots liked to be dominated.

In this phallocentric realm of control, Nicosia’s cabaret industry thrived as urbanisation and a heavy military presence overwhelmed the old side-alley brothels, with the house girls especially popular with the ‘Cabaret Government of Cyprus’ (Constantinou: 286). Then, between 1955 and 1959, during the vicious, chauvinistic campaign by EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston/National Organisation of Cypriot Fighters) for an end to British rule and union with Greece, the image of Venus became a contested one. For EOKA, the goddess was easy propaganda, her Hellenic form of Aphrodite a sure indicator of what they saw as the island’s eternally Greek nature, justifying independence from Britain and union with the ‘motherland’.

British soldiers and civilians were dying at the hands of EOKA in those ‘emergency years’ and, coincidentally or not, the previously-overlooked issue of prostitution became a concern for the British press too. In the collective psyche, this was again a hazardous place of sexual indecency, just as it was in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This time, however, that perception had effects beyond the stage and the page.

Further, responding to EOKA’s reclamation of the goddess, the colonial government championed her more explicitly Middle Eastern incarnation, Astarte. Late nineteenth-century visitors to Cyprus had often chosen Astarte, rather than Venus, as most appropriate to an island they considered as a non-European site, neither Greek nor Turkish. William Hepworth Dixon said it most straightforwardly: ‘In blood and race both men are Cypriotes’ (20). This was Cyprus as a standalone Middle Eastern site, with the pan-Mesopotamian Astarte as its emblem of diversity. But the colonial administration shifted the emphasis.

Elizabeth Alicia Maria Lewis wrote that Cypriots were more like Astarte than the Europeanised Venus of Punch because, like Astarte, they were ‘oriental’. By this, Lewis meant they were ‘slothful, mendacious, voluptuous’ (202). It was this analogy that the ‘Cabaret Government of Cyprus’ picked up on, an analogy that painted Cypriots as morally degenerate and racially impure, bolting genetic corruption onto the goddess’s ancient immorality. And the morally degenerate and genetically impure cannot govern themselves (see Given: 419–23; Papadakis: 239–40). They’re asking for domination, whether they know it or not. A recent batch of Foreign and Commonwealth Office files released to The National Archives lays bare the intention to polarise the island’s largest communities as racially incompatible, a process that would have to be ‘artificially induced [. . .] over a period of ten years or more’ (The National Archives, FCO 141/4363: ‘Partition’).

It is this vision of Greek-speaking Christians and Turkish-speaking Muslims as diametrically opposed, of their union as impossible miscegenation, which has led to the island’s division since the war of 1974. Those ‘artificially induced’ oppositions – enthusiastically adopted by fanatical Greek and Turkish nationalists and manufactured during British rule – are now so deep-rooted that the July 2017 collapse of the most recent UN-brokered talks for reunification were as unsurprising as they were upsetting. The erotic, bawdy myths surrounding Venus that were titillating inspiration for Shakespeare and other early modern writers have a very different political afterlife on the island, one that contributed to its devastation and ongoing division.

Roger Christofides

Constantinou, A. C. (2013), ‘Cyprus and the Global Polemics of Sex Trade and Sex Trafficking: Colonial and Postcolonial Connections’, International Criminal Justice Review, 23 (3): 280–94.

Dixon, W. H. (1879), British Cyprus, London: Chapman & Hall.

Given, M. (2002), ‘Corrupting Aphrodite: Colonialist Interpretations of the Cyprian Goddess’, in D. Bolger and N. Serwint (eds.), Engendering Aphrodite: Women and Society in Ancient Cyprus, 419–28, Boston, MA: American Schools of Oriental Research.

Lewis, E. A. M. (1894), A Lady’s Impression of Cyprus in 1893, London: Remington.

Papadakis, Y. (2006), ‘Aphrodite Delights’, Postcolonial Studies, 9 (3): 237–50.