On Calle Alfonso XII, immediately after Plaza Duque de la Victoria, stand the remains of what was once one of the main references for many English visitors to Seville: the Jesuit College of St. Gregory. Founded on 12 November 1592 by Robert Parsonio, the ‘arch-Jesuit’ feared by the Elizabethan authorities, the college was destined for English students who would be trained to serve in the dangerous Jesuit missions in England. Like the English colleges in Italy or France, the college in Seville offers insight into the lives of English Catholics outside England itself. While state discourse in the post-Reformation period was continually scattered with paranoid references to the networks of Catholic alliances beyond England, TIDE’s recent visit to the college in Seville prompted my curiosity about what the English actually did when they went to study and teach in European colleges, and how this informed both English and Spanish fears about orthodoxy and political stability.

Encouraged by the success of The Royal College of St. Alban, founded in 1589, Roberto Parsonio, as he was known by the Spanish, believed that Seville’s privileged position as the main hub of Spanish colonial trade had the potential to offer to the English Jesuits a much welcomed access to wealthy patrons and to the necessary logistics to travel with relative safety to England. It is interesting to note that the reasons behind Parson’s decision to establish an English college in a busy and wealthy port city like Seville were the same that led many of his Spanish companions to avoid investing in public education. Despite its importance and prosperity, Seville lacked a major university, though the University of Seville was founded in 1505. In 1570, the Andalusian provincial explained that the hesitations of the Jesuits were motivated by the ‘acute but volatile Sevillian mind’. Young Sevillians, wrote the provincial, were ‘brought up in affluence, idleness and luxury’. The city was a place where ‘every day brings many novelties from the land and the sea which distracts the youth from their studies’. This made Seville, as well as all other large urban centres and port cities, ‘incapacitated for learning, because there are many distractions, and many opportunities for vices, carnal joys and continuous novelties’. The provincial’s observations on the Sevillian character, however, seemed to hide another problem: the quality of the few students who entered the only grammar school run by the Jesuits in Seville, and who were described as ‘poor and uncultured’.

Parsons founded St. Gregory’s in a period when Jesuit social and intellectual prestige was boosting in Seville. The Spanish Crown expressed an inclination to help English Catholic exiles for both religious and political reasons. Philip II supported the foundation of St. Gregory’s, and the powerful dukes of Medina Sidonia were among the protectors of the Colegio de los Ingleses. If the political and financial support granted by the Spanish monarchy and grandees ensured the immediate success of the college, the decision of Pope Clement VIII in 1594 to grant to St. Gregory’s the same degrees and titles previously conceded by the Church to Oxford and Cambridge bolstered the prestige of the college.

Also in 1594, St. Gregory’s began to gain the reputation of a cradle for martyrs following the death of one of the college founders and teachers, Henry Walpole, who was executed in London and acclaimed a martyr by the Jesuits. Walpole’s celebrated martyrdom was followed by the death of two students, Robert Waller and Thomas Egerton, for excessive penitence in 1595. In 1600, Thomas Hunt was the first St. Gregory’s graduate to be executed in England. These first martyrs of the Colegio de los Ingleses generated a popular veneration throughout Seville and the rest of Andalusia. Sevillians, wrote Parsons, looked to St. Gregory’s ‘with a kind of admiration of them, to see many Inglish tender youthe al bred and borne in this Queene’s reign and yet so forward and fervent in their religion as to offer themselves to al kinde of difficulties, afflictions and perils of the same’.

The arrest and execution of Henry Walpole in 1594 led the Elizabethan authorities to regard the Colegio de los Ingleses as potential platform for ‘popish’ conspiracies organised by English Catholics with the help of Spain. During his examination, Walpole indicated that St. Gregory’s contained 40 English students, but refused to reveal their names. The college was at times a harbinger of political radicalism – in 1597, it was associated with a supposed plot to assassinate Queen Elizabeth, which involved a former English prisoner of the Sevillian Inquisition and the Jesuit Richard Walpole. The plot consisted of poisoning the queen’s gloves with perfume, taking advantage of knowledge about poison, and links to the household of the earl of Essex.

The reputation of the college as politically and religiously subversive was reinforced by the recurrent employment of the members of St. Gregory’s as interpreters for the Sevillian Inquisition. Parsons and the administrators of the college always sought to establish good relations with the Holy Office in order to avoid any sort of suspicion regarding the presence of young Englishmen at Seville, who could be under the influence of heretical ideas. The students of St. Gregory’s were often enthusiastic supporters of the Inquisition. In 1616, Francisco Peralta, the rector of St. Gregory’s, mentioned that one student who was being sent to England, had earlier thanked the Inquisition for protecting the college and declared his desire to see the Holy Office ‘establish in England and other provinces plagued by heresy, in order that by its means religion might be kept pure and undefiled as it was in Spain’.

In spite of their adherence to Catholic orthodoxy, some sectors of the Spanish Church feared that the English Jesuits could not be trusted for coming from a heretic country. Most of these fears originated in xenophobic feelings which depicted the English as a people of ‘barbarous customes and manners’, or conspiracy theories that suggested that the English students of the Valladolid and Seville colleges were spies that wanted to destabilise Spain and spread Protestantism across Iberia.

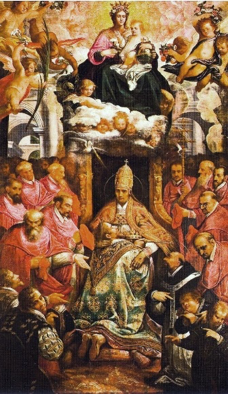

St. Gregory’s reputation as cradle of martyrs and a bastion of the Counter-Reformation was reflected by the artworks that decorated the college and its church. Painting such as the anonymous Virgen de los Ingleses (1593) or Juan de Roela’s El Triunfo de San Gregorio (1608) represented the prestige of the college, as well as it allowed the English Jesuits to develop an interesting narrative of a devoted Catholic England which would eventually triumph over Protestantism. This message was also transmitted in the pamphlets, accounts, poems and plays written by the members of the Colegio de los Ingleses. Ballads and poems dedicated to St. Gregory’s martyrs such as Henry Walpole and other Catholics executed in England were especially popular. The college was also famous for the plays staged by its members which usually attracted a considerable audience and offered a much welcomed source of revenues.

Money was often a problem for the Colegio de los Ingleses. Though Parsons gained the patronage of Philip II and the Andalusian grandees, the gradual improvement on Anglo-Spanish relations after the ascension of James I, and Parson’s death in 1610, had a profound impact on the wealth and fortunes of the college. As Spain tacitly recognised the triumph of Protestantism in England, St. Gregory’s role as a bastion of English Catholicism lost much of its appeal. Without the capacity to attract wealthy and influential sponsors, the survival of the Colegio de los Ingleses often relied on the alms collected by students in the streets of Seville or Cadiz. One 1626 account of the college mentioned that the alumni of St. Gregory’s sold images of St. Thomas Becket and St. Thomas of Canterbury to the crews of the ships that sailed from the Andalusian ports to the Americas.

Towards the middle of the seventeenth century, Seville also started a slow decline which accelerated the college’s decay. In 1626, the great flood of the Guadalquivir River caused serious damage to the college buildings. The great plague of 1649 decimated a considerable number of students and staff. In order to maintain its existence, the college began to accept Spanish, Irish, and other foreign students. In 1662, the college counted with only five students; in 1692, only two. A year later, there were no English students at St. Gregory’s. The suppression of the Society of Jesus in 1767 was the final death blow of the Colegio de los Ingleses. After the expulsion of the Jesuits from Spain, part of the buildings of St. Gregory’s served as the headquarters of the Real Academia de Medicina of Seville until 1932, when, due to the poor state of the buildings, the buildings were demolished and replace by the present School of Hispanic-American Studies. The church, however, survived, and was leased to the Hermandad del Santo Entierro, one of the brotherhoods of the Sevillian Holy Week, and is today the headquarters of the Mercedarians at Seville.

Today the remains of St. Gregory’s no longer suggest an English presence. But just a few metres from the old Jesuit college and church stands the biggest department store of Seville: El Corte Inglés, ‘the English cut [tailoring]’, on a street where the presence of the English therefore continues to linger.

João Vicente Melo