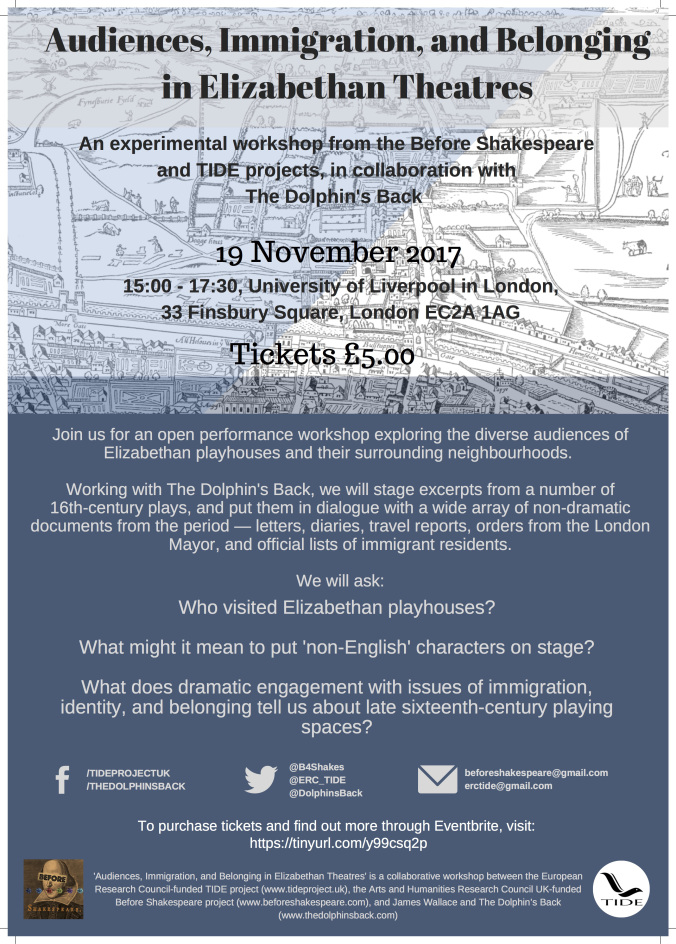

On the 19th November 2017, the TIDE project and Before Shakespeare are hosting a workshop exploring the diverse audiences of Elizabethan playhouses and their surrounding neighbourhoods, based at the University of Liverpool’s London campus, 33 Finsbury Square. Working with The Dolphin’s Back, we will be looking at a range of plays, archival documents, diaries, and other materials to ask: Who visited Elizabethan playhouses? What might it mean to put non-English characters on stage? What does dramatic engagement with issues of immigration, identity, and belonging tell us about sixteenth-century playing spaces? This blog takes us back to the site of that workshop some four hundred odd years ago, in order to think about the neighbourhoods on the doorstep.

Today, in the heart of the City and amid its glassy towers, Finsbury Square smacks more of balance books than playbooks. Yet it is at the heart of London’s long and crucial history of cosmopolitanism.

Elizabethan England had a mixed relationship with immigration. It welcomed religious refugees and offered patents to immigrant craftspeople settling in the country. At the same time, there were considerable tensions about non-English labour and the government recorded lists of immigrants, demanding reasons for their living in England, their occupation, and their religious proclivities. These recorded lists are often known as the “Returns of Strangers.” In early modern England, “stranger” was a flexible term, but here can be defined as a foreign-born individual resident in a particular parish or community. The mixture of resentment, distrust, fear, and othering often resulted in the persecution of immigrant settlers and their communities.

Here, we introduce some of the Londoners who lived in the surrounding neighbourhoods, ahead of exploring their fictional equivalents in the drama of the late sixteenth century and their and others’ real-life presence among the audiences and neighbourhoods of early playing spaces.

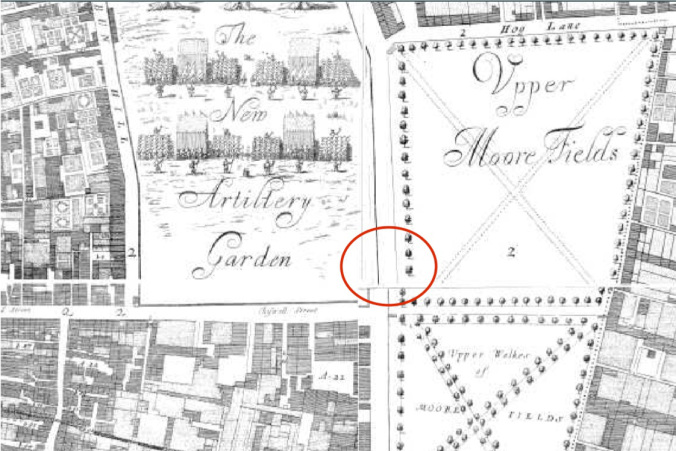

![Roughly on the spot of what is later known as “Upper Moorfields” and in the area known in the 1570s and 1580s as the recreational land Finsbury Fields (just north of Moorfield and the ditches outside the city wall). To the left was the neighbourhood north of Cripplegate and to the right the growing neighbourhoods north of Bishopsgate, whose main road extended north from the church of St Botolph’s without Bishopsgate, past Bedlam Hospital, into Norton Folgate, and north through Holywell and St Leonard’s parish in Shoreditch. Section of “Plan of London (circa 1560 to 1570),” in Agas Map of London 1561 ([s.l.], 1633), British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/london-map-agas/1561/map [accessed 22 October 2017].](http://www.tideproject.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/Picture1.jpg)

The characters populating the neighbourhoods around Moorgate and who live in the vicinity of the playhouses in Shoreditch are an important factor in thinking about the rise of commercial playing, not least when a number of the earliest plays surviving from those playhouses prominently feature “strangers,” black men and women, European merchants, and debates about the economic, social, and cultural consequences of immigration in London.

Some of the individuals living in and around Moorgate, Bishopsgate, Norton Folgate, and Shoreditch offer intriguing connections between the city and the stage. Robert Wilson is found resident in the parish of St Botolph’s Without Bishopsgate in the 1580s, when he is described in a legal case, rather conspicuously, as a “player” (LMA MJ/SR/0258/56). He appeared alongside fellow actor John Dutton in a tax return for the parish in 1582 and 1587 (TNA E179/251/16, TNA E115/118/24, and E115/403/110).

A few minutes up the road in Norton Folgate, Wilson might have come across one Peter Rastringinge, a buttonmaker from France and his wife Margaret, both born in Armentiers and having lived in England for 12 years. There may well have been a local edge, therefore, to Wilson’s depiction of the character Fraud in his play from the late 1580s, The Three Lords and Ladies of London. In that play, Fraud takes on a disguise as an “artificer” from France, who is selling various gilded buttons. Far from being an outlandish satire or send-up of a foreign merchant, Fraud’s deception speaks very literally to the type of individual audiences would have seen or known. Perhaps Peter Rastringinge, his wife, colleagues, or fellow countrypeople would have seen the play themselves, begging the question of how self-consciously such an episode might have been performed or how inclusive or exclusive such a spectacle might be.

The notion of an “English” person is itself up for debate in this period. London’s city council periodically took pains throughout the 1570s and 1580s to make it clear that children of immigrants retained an immigrant status themselves. These questions are at issue in plays that interrogate the issue of nationhood—including those featuring Englishmen fighting abroad on the behalf of foreign princes, such as George Peele’s The Battle of Alcazar—and also in plays that explicitly think about generational difference itself. In The Three Ladies of London, the eponymous ladies have a more complex relationship to their city and country than the title might initially suggest, as do surrounding characters. Lucre’s grandmother is, audiences are informed, Venetian, and we learn that she is in fact a second- or third-generation immigrant to London. She in turn enquires of Usury, “why came thou to England?”, and Usury replies:

"I have often heard your good grandmother tell,

That she had in England a daughter, which her far did excell:

And that England was such a place for Lucre to bide,

As was not in Europe and the whole world beside...”

In the same exchange, Simony recounts his birth in Rome, where he dwelled with monks and friars, before “they invited me / with certain other English merchants” to visit England.

Exactly this question of generational status, nationhood, and belonging is at issue outside the playhouse. Again, in the same parish as the The Three Ladies’s author, Thomas Wilson, a clerk noted in 1586 the case of a mixed-race child—the baptism of ‘Elizabeth, a negro child, born white, the mother a negro’ (GL MS 4515/1). What exactly is meant by such a description remains unclear. However, the notion of a ‘negro child, born white’ highlights the complicated perceptions early modern Englishmen and women had of identity, status, and indeed the legibility or visibility of an otherness that the parish clerk is keen to mark out. A year later a little further east, at St Botolph Aldgate, twenty-year-old ‘Mary Phillis of Morisco, being a blackmore’ was baptized (GL Ms 9234/6). The parish clerk in detail also noted down Mary’s conversion narrative, describing how she had been in the country for between thirteen and fifteen years after living with ‘one Millicent Porter a seamster’ and was now ‘desyrous to becom a Christian.’

Indeed, the area around St Botolph’s included one of England earliest black communities. On the 22 October 1586, 'Christopher Cappervert, a blacke moore' was buried at the church (Guildhall Library [GL] MS 9222/1). The term blackamoor most often referred to an individual from Sub-Saharan Africa, and put colour at the heart of early modern English conceptions of identity. In his 1600 translation of the North African humanist scholar Leo Africanus’ Description of Africa, John Pory described the ‘principall nations’ of Africa as including ‘the Africans or Moores, properly so called; which last are of two kinds, namely white or tawnie Moores, and Negros or black Moores’(Pory, The History and Description of Africa Ed. Robert Brown, 1896, 20). Grammars and dictionaries of the time made similar associations: ‘The Negro’s [sic], which we call the Black-mores’ (Ralegh, The history of the world, 1614, L2r.)

The following year, 'Domingo, beinge a Ginnye negaro and beinge servaunt to the Right Worshipfull Sir William Winter' was also buried at St Botolph’s after succumbing to consumption (tuberculosis) (GL MS 9234/1, f.127v). Between 1586 and 1596, 8 black men and women were registered by the parish clerk at St Botolph’s as being buried, including 'Suzanna Peavis a blackamore servant to John Deppinois’ (GL MS 9221/1) and a black man 'suposed to be named Frauncis' who was a 'servant to Peter Miller a beare brewer” (GL MS 9223). In 1594, close by in St Stephen Coleman Street (now Gresham Steet), a black woman named 'Katernine' who had been 'dwelling with the Prince of Portingal' was buried (GL MS 28867).

The neighbourhood of St Botolph’s was also home to a variety of European immigrants, including one Peter Favale, 'of Bolyuia de Grace' and one Poll Germall, a Genovese gentleman who lives with Favale. They both attended the English church and had been in the country 30 and 10 years respectively. Individuals also circulated between city and court life. The parish was home to John Baptist Violer, a servant of Queen Elizabeth. Searches have afforded little information about 'Violer,' and 'John Baptist' is a popular name, including among stranger preachers. There is, though, another John Baptist, of Castiglione, who also had status in the royal household at this time; Giovanni Battista Castiglione is described in a letter to Emperor Ferdinand in 1558 as 'one of [Queen Elizabeth’s] favourite and private chamberlains' (qtd Bolland 42, 'Alla Prudentissima' in Leadership and Elizabethan Culture, Ed. Peter Iver Kaufman, 2013). He formed part of a small network of individuals in royal circles the early years of Elizabeth’s reign, and Thomas Blundeville’s dedication to Leicester of an advice manual, A Very brief and profitable treatise, printed in 1570 thanks 'my very friend Mayster John Baptist Castiglion one of the Gromes of hir Highnesse privy chamber' (A2v). The St Botolph’s John Baptist, however, is likely a different man, given his suffix, 'Violer.' Other court-associated immigrants were present down the road in St Alphege parish (in Cripplegate, near the London wall), where Frauncisco Ytalion and Ambrose Ytalion could be found, both musicians to the Queen who had dwelt in England 27 and 30 years respectively by the year 1571.

Moregate, Cripplegate, Shoreditch, and the areas around them are examples of the mixed reception of stranger communities in England. They were home to many foreign artisans, particularly silkweavers. These silkweavers came from various parts of Europe, including a number born in Valencia who dwelt in Shoreditch at St Leonard’s parish in the early 1580s. A list of immigrants from 1571 included one John Deboyse, a Frenchman, who had the curious occupation of 'morispykemaker' (that is, Moorish Pike-Maker, a weapon); he was a denizen and member of the French church.

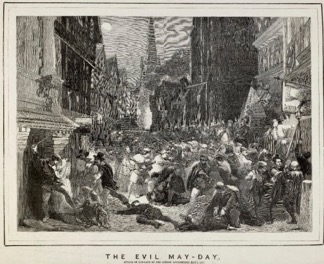

In some cases, as strangers increasingly settled in these areas in London, anti-immigrant sentiment increased amongst the English population. The most notorious of these incidents were the Evil May Day Riots of 1517, the first documented race riot and worst case of violence against immigrants in early modern London.

Evil May Day is at the centre of the Elizabethan play The boke of Sir Thomas More (which survives in a manuscript composed and revised between c. 1593 and 1600 by Munday, Chettle, Dekker, Heywood, Shakespeare), itself coming out of and responding to increased tensions between English Londoners and “strangers” in the 1590s. In 1517, the areas surrounding Moregate, including Cripplegate, Bishopsgate and Aldgate, did not escape the violence that ripped through London, both during and after the riot, as gallows were erected at the main sites of the riot to execute the perpetrators.

It is not only men who characterise the occupations of these lists of immigrant residents. Norton Folgate was also home to a widow and denizen, Thomasine Barny, who “useth shoemaking.” She was born in “Ortwayes"—perhaps Orthez, in the south west of France, which had a substantial Protestant/Huguenot population and a Calvinist-leaning university; it was also the centre of some gruelling fighting during the conflicts between Catholics and Protestants in France, including a major battle (won by the Huguenots) in 1569. Barny had lived in England for 15 years and had two (likely French) servants, John Morsonne and Jakery du Roye (Returns 2: 369). The authority, skills, and commercial savvy of the three ladies in Wilson’s play have their counterparts in the city of London, too.

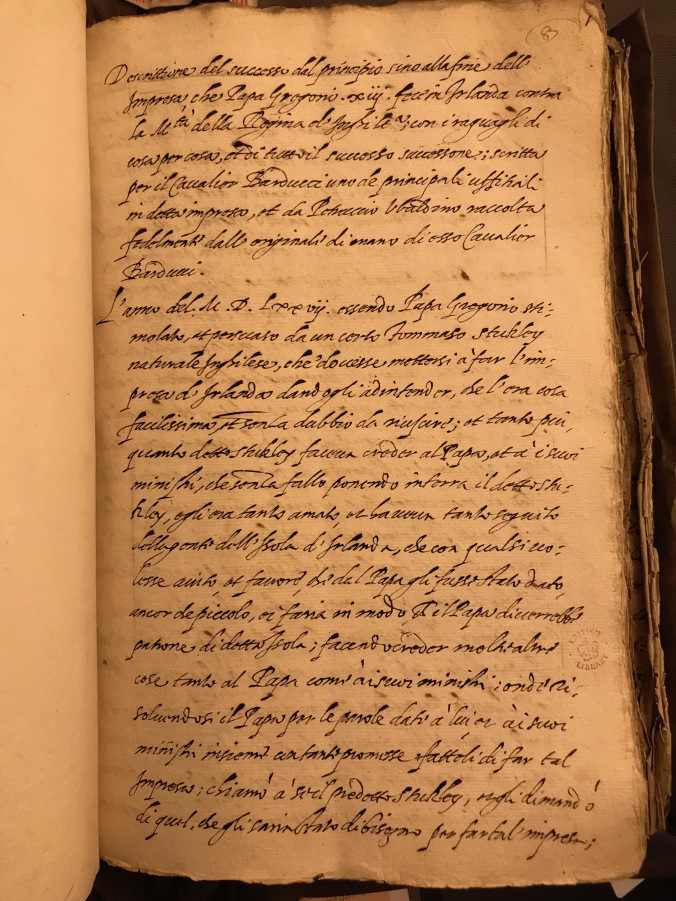

Up to the east of Finsbury in Hallywell Street in 1583 lived Petruccio Ubaldino, noted in the list of names “of all the Straungers inhabiting within the Precinct of Hallywell Streete” as “an Italian, a gentleman belonging to the Courte, hath been here 27 years” (2: 367). Ubaldini was a soldier who came to England in the 1540s, and he worked as an illuminator while also writing and translating texts. In his years in England in the 1560s, Ubaldini taught Italian and acted in comedies at court, as well as transcribing letters and eventually working on state business across Europe (for more details see ODNB, Cecil H. Clough).

Ubaldini, while being an actor himself, also provides some of the background material for one of the Elizabethan stage’s prominent characters, Thomas Stuckley. Stuckley worked abroad for foreign princes, and features in Peele’s play The Battle of Alcazar fighting for the Spanish. Ubaldini had written for Lord Burghley an account of Gregory XIII’s invasion of Ireland, which started under this infamous Englishman-abroad, in 1577 (TNA SP 9/102 and BL Add. MS 48082, fos. 87-121).

The area outside and around Cripplegate was home for some years to one Francis Marquino. He is described in 1571 as a “sylkworker,” an occupation he shared with many of his European neighbours, and he lives in (St Michael’s) Wood Street in 1571 with his wife, Levena, having been in England for 12 years. He is noted that year to be a denizen and member of the Dutch church, and he and Levena had 4 children. In 1576, he is to be found in St Peter’s Cripplegate, and by 1583 he has seemingly established an international school in Shoreditch or Hoxton. The list of strangers in the area for that year describes him as a “scolemaster” born in Lombardy, living with Levina (or Lavinia) and now with 8 children (all born in England). He “hath 24 scholars, strangers’ sons, born in England,” as well as an usher named Peter Hurblock (2: 370). It is curious to think that Lavinia and her family may have been part of an early audience for Shakespeare’s Titus Andronicus, which includes the brutal rape and mutilation of Titus’s daughter, Lavinia. While the Roman and “foreign” subject-matter of Shakespeare’s plays is often said to distance the content from England itself, these names were not wholly exotic and echoed the communities on the doorsteps of playhouses and playwrights.

Francis Marquino, like Ubaldini, also worked as a translator for the printer John Wolfe: he rendered A politike discourse most excellent for this time present: composed by a French gentleman, against those of the League, which went about to perswade the King to breake the allyance with England, and to confirme it with Spaine into English for publication in 1589 (STC 13101). Beyond this, there seems to be little more information about his life. His apparent change of profession may be due to an error in the 1571 return or a new direction for Marquino. (Francis and Lavinia are noted with little information in 1560 and 1561; in the latter list of attendees of the Dutch church, Francis Marquino is called a “caligarius”—a shoemaker—adding confusion to his profession or suggesting a man who liked to change trades (1:274).) The substantial information provided in the 1583 return, however, gives the details particular weight, and a sizeable “stranger” school for second-generation immigrants in the suburbs surrounding Finsbury and the Shoreditch playhouses gives fascinating texture to our understanding of the neighbourhoods north of Bishopsgate.

All of these individuals live in the vicinity of various leisure pursuits surrounding Moorfield. John Stow’s Survey of London (1598) explains that Moorfield was used for recreational activity, in particular walking, shooting, and wrestling. During Henry VIII’s reign, the area was enclosed and populated with impressive summerhouses. In the later sixteenth century, further beyond Finsbury lay part of London’s waste disposal system, and Stow bemoans the “laystalls of dung” with three windmills placed on top, around which “the ditches be filled up, and the bridges overwhelmed” (Z8v). In the later years of the sixteenth century, these areas north of the walls underwent a period of change and growth, especially in the burgeoning suburban neighbourhoods to the east and west of Moorfield and Finsbury. Seeing these surroundings populated by French weapon-makers, Italian courtiers, and black men, women, and children speaks to the diversity of London but also underscores some of the issues about identity, nationhood, and belonging at the heart of so many Elizabethan plays.

We look forward to exploring the role of immigration in Elizabethan plays, thinking about who formed their audiences, and contemplating the sentiment of belonging in these contexts on the 19th November. If you would like to join us, tickets are available on Eventbrite.

Works Cited:

Clough, Cecil H. “Ubaldini, Petruccio.” Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Online. Web. 3 Nov. 2017.

Kirk and Kirk, eds. Returns of Aliens Dwelling in the City and Suburbs of London. Parts 1-2. Huguenot Society of London, UP, 1902.

Leadership and Elizabethan Culture, Ed. Peter Iver Kaufman. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Stow, John. Survey of London. London, 1598. Early English Books Online. Web. 3 Nov. 2017.

Wyatt, Michael. The Italian Encounter with Tudor England: A Cultural Politics of Translation. Cambridge UP, 2005.