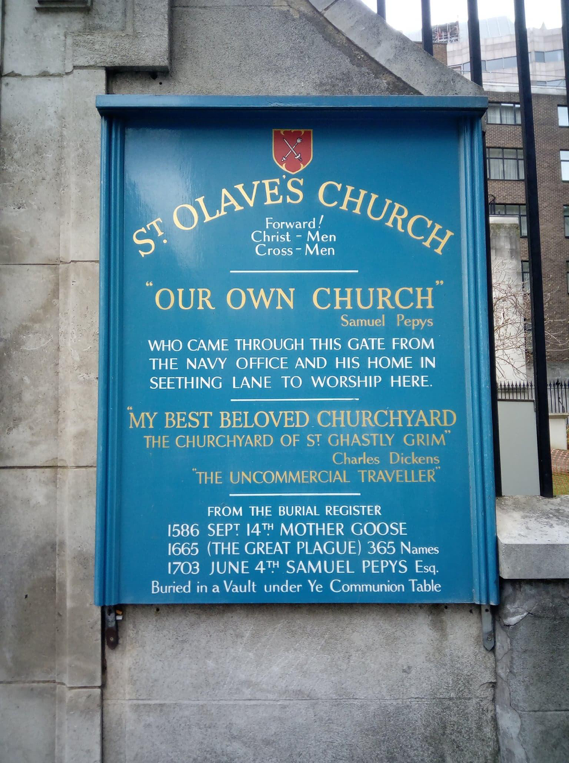

'My Best Beloved Churchyard', wrote Charles Dickens of St Olave's Hart Street in The Uncommercial Traveller. The plaque outside the parish church on Seething Lane in London's financial district offers a smorgasbord of tempting historical ties. None other than 'MOTHER GOOSE' was interred here in September 1586, and three hundred and sixty-five victims of the Great Plague of 1665 were recorded in the burial register. Samuel Pepys Esq., prodigious diarist and cheese enthusiast, was 'Buried in a vault under Ye Communion Table'. Traces of the parish's early modern life surround the church; opposite sits Walsingham house, the family home of Queen Elizabeth's Lord Secretary. Once the headquarters the Tudor State's vast intelligence network, it's currently undergoing a transformation into much needed office space. To the immediate north of Walsingham House sits the Crutched Friars pub, a happy memorial to the Carmelite monastery that stood along the eponymous street, dissolved under Henry and destroyed by the Fire.

Unobserved, but deserving of attention, is the fate of the repurposed monastery buildings between these two events. It was in the hall of the Crutched Friars that the Venetian Jacob Verzelini established a furnace in the early 1570s for the production of a luxury commodity that captured the imagination and loosened the purse strings of England's wealthy elite. Produced using silica, manganese, and soda plant-ash from the Levant, Venetian glass (cristallo) was renowned across Europe for its exceptional transparency, and it appears in English royal and aristocratic household inventories from across the Tudor period. Such was the value of this crystal that when Thomas Howard, 4th Duke of Norfolk was sentenced to death in 1571 for his involvement in the Ridolfi Plot, he bequeathed Sir Nicholas Bacon, Sir Walter Mildmay, and Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester a single piece of crystal glassware each.

The production of cristallo in England dates back to 1549, when Edward VI invited eight Muranese glassmakers and several Dutchman to establish a furnace near Belsize park in an effort to internalise manufacturing. The emigration of glassworkers had long been forbade by the Venetian authorities, who, on receipt of the knowledge of this trade infringement, demanded their return. In an effort to broker an agreement, the workers were imprisoned in the Tower, where they remained until 1551. All but two returned across the Channel: Guiseppe Casselari and the Dutchman Thomas Cavato. Internal production abated for a while, and in 1558, William Harrison marvelled in his Description of England at the currency of 'Venice glasses' among the rich and powerful, who, as 'is the nature of man generallie [...] most coveteth things difficult to be attained'. Many became 'rich onlie with their new trade unto Murana', writes Harrison, although records do not indicate extensive importing, at least among the English merchants. Just one instance is recorded in the 1567/8 book of imports for London: the English merchant Nicholas Spering, a purveyor of luxury European commodities, imported ’35 doz. crystall glasses’ amongst other items from Antwerp in a vessel carrying the cargoes of sixty-seven other individuals. They may have come in on the galleys of resident Venetians or Genoese, who despite the gradual decline of Italian control of English foreign trade during the sixteenth-century, still dominated Venetian imports. Yet only one fragmented port book survives for the merchant strangers, who kept separate records of ships and cargoes to the native English, and it is too incomplete to garner a thorough analysis.

Yet the English market for glassware was lucrative enough to encourage immigration from the continent. Before coming to London in 1567, John Carré, a native of Arras, France, was a manufacturer of window-glass in Antwerp. He possessed a shrewd grasp of the market and once settled in England wasted no time in requesting a patent from the Privy Council for the production of both window-glass and Venetian-style crystal for drinking vessels. The application chimed with assurances of locally-sourced materials; everything was to be found within the realm, bar the soda, which must be imported from Spain. He had even already erected a fit for purpose furnace in the City by leave of the Lord Mayor. A monopoly over window-glass was granted, with the proviso that he also trains Englishmen in the skill so that upon expiration, production can continue under native workmen. A monopoly over Venetian glassware, however, was denied.

Carré continued in his cristallo venture anyway, and it appears that by 1570, the furnace was up and running. He may have used his Antwerp connections to bring in the Venetian Ogniabene Luteri to work alongside the veteran Casselari; by December that year, another seven Muranese workmen resided with Carré in the parish of St Benet Fink, Broad Street Ward: Vincent Figlio, Dominic Casselari (potentially a relative of Guiseppe), Marco Guardo, Lawrence Farlonger, Francis Gilio, Biasio Brandarmin (or Brandium), and John Morato. It has long been asserted that Carre was the first proprietor of the glasshouse at the Crutched Friars, although this is uncertain. The fact that both he and his workers lived in St Benet Fink, as opposed to St Olave’s in Hart Street, may suggest that the furnace Carré presumptuously built was located in the north of the City. He also relocated to the parish sometime in the same year as his license application, having previously resided further south near the river in the parish of St Swithen’s, Walbrook Ward. This may be coincidence, but it is worth noting that other Venetian glassblowers connected to the Frenchman's venture also occupied rooms in the parish.

Carré died in 1572. Responsibility for the glasshouse was formally charged to his brother-in-law Peter Campe and his son John Baptist, who were instructed to ‘accomplisht the contract’ made between the dying glassmaker and ‘the Italyans’. Although John Baptist would later operate a furnace in Surrey, it appears that neither party continued to produce glass within the capital. The opportunity was thus presented to the savvy Verzelini to invest in the lucrative business. He had left Venice for Antwerp in the 1550s, where his brother Nicholas was possibly already established in the glass business. He achieved not insubstantial success, as in September 1556 married the minor aristocrat Elizabeth Vanburen, of the House of Mace on her mother's side. Jacob and Elizabeth's movements following their marriage are unclear. Both 1565 and 1570 have been posited as a possible date for their arrival in London, although surviving records indicate that a Venetian surgeon by the name of Jacob Fraunces was a resident of St Olave's Hart Street parish in 1564, and there is reason to believe he and Verzelini are the same person. Fraunces still lived in the parish alongside his wife Elizabeth in 1567, and is found there again in May 1571, this time by the name of Jacob 'Frauncevercelyno'. By November, the alias or middle-name 'Fraunces' had been dropped, and he is found working as a broker, possibly in connection with his brother in Antwerp. He appears to have continued practising as a surgeon throughout his life, and was well-regarded in the profession. During the birth of Robert Sidney, future Earl of Leicester in November 1595, the family physician Doctor Browne took the precaution of sending for the now seventy-three-year-old 'Jacob of the glasshouse' in case of complications.

Sometime between 1572 and 1574, Verzelini had 'sette uppe within [London] one furneys and set of worke dyvers and sondrie parsonnes' in the hall of the Crutched Friars. He secured a patent over cristallo manufacturing with the same proviso as Carre: that Englishmen are trained to continue production upon expiry. For at least the next ten years, however, all those employed appear to have been Venetian. These 'parsonnes' included three of Carré’s workers, Vincent Figlio, Dominic Casselari, and Marco Guardo, who had relocated to St Olave’s Hart Street to live alongside the newly employed Venetians Zatario Brunoro, Satario Moro, Augustin Corona, Marcas Fingamo, Jerolimo Fero, and Baptista Sorte. With this new influx of workers, St Olave's Hart Street became the most concentrated area of Italian immigrants in the city. Vincenzo Guicciardini, the herring exporter, occupied rooms near the church on Seething Lane. Acerbo Velutelli, the exceptionally wealthy Lucchese merchant and close friend of Leicester, resided next door with his five servants: Hippolito, Ascania, and Scipio Velutelli, as well as the Venetian Racheo de Vitello and the Frenchman, John Vidale. Other Italian merchants, factors, and servants all lived and worked within close proximity to the glasshouse. While most of these men have left few traces, evidence of their sociability can be found both directly and indirectly in records pertaining to well-connected Italians.

During the New Year's Celebrations at court in 1577/8, the musician Marc Antonio Galliardo, of neighbouring Portsoken Ward, presented the Queen with 'a viall'; the following year, he gifted 'four Venyse glasses'. Younger members of the Italian dynasties who dominated court music during Elizabeth's reign can be found associating with glasshouse workers. In August 1581, the court musician Joseph Lupo was interrogated by the Consistory of the Italian Church in London on the activities of the silk-dyer Gasperin de Gatti of St Martin Vintry, Vintry Ward, who had been accused of consulting a ‘sorcerer’. Lupo was walking through Crutched Friars when he stopped to talk with Elizabeth Verzelini outside of the glasshouse. Verzelini informed him that de Gatti’s boiler was broken and the tincture was not taking to the material. He believed that they had been enchanted and as such had sent a servant to consult a woman in Rochester on how to lift the enchantment. In August 1585, the court musician Marc Antonio Bassano, son of Alvise, was conversing with the London weaver Valentine Wood and two of Verzelini’s men just beyond Aldgate when they he was attacked and nearly slain by a group of soldiers who took them for Spaniards.

Anti-alien sentiment was not limited to isolated acts of violence. The Crown and City were often at odds in the period over the economic freedoms to be extended to immigrants who took up residence in capital. The latter, concerned with the trade infringements on its constituent Guilds, enacted stringent measures that severely limited the retail practices of stranger craftsmen. Immigrants were prohibited from trading with anyone who was not a freeman of the City of London, a regulation that Verzelini fell afoul of in 1579 when he sold glass to a 'foreigner' from Leicester. The Crown, however, recognised the financial benefit of skilled immigrant labour, particularly that of liberal artisans who catered to the Italian cultural vogue at court. At the interjection of the Privy Council - possibly championed by Robert Dudley, the great defender of England's Italians - Verzelini's glasses were restored. Again in 1581, the Privy Council argued the glasshouse keepers case when one Sebastian Orlandini, a glassblower from Venice, infringed on Verzelini's monopoly by producing cristallo goblets in his furnace at Beckley near Rye.

On occasion, anti-alien sentiment boiled over into acts of violence or destruction of property by English workmen and competitors. Angered by the sudden requirement of to a license fee made payable to Verzelini on all Venetian glass imports, it may have been shopkeepers who started the fire that burned the furnace to the ground 4 September 1575. Fed by an adjoining storeroom containing forty thousand billets of wood, only the buildings outer stone wall prevented the blaze from spreading. Verzelini was forced to set his men working at a temporary furnace at Newgate while the Crutched Friars was rebuilt.

The glasshouse was reopened in 1579, and Verzelini continued to run manufacturing until his retirement in 1592. It is difficult to attribute the dozen extant glasses from the Venetian's furnace to any original owners, although two have ties to aristocratic patrons. The British Museum hold a tankard with silver-gilt lid and base (c.1574) which may have belonged to William Cecil, Lord Burleigh, and a note in an eighteenth-century hand was found in a leather case holding a crystal cup that reads: 'This glass belong'd to Queen Elizabeth, out of which she drank: It has been in Mr Vicker's family Time after mind. In 1726 I was married to Mr Vickers'.

The popularity of his glassware made Verzelini a rich man, and upon his retirement he moved to his large estate in Downe, Kent. It appears that his sons were charged with continuing the business, although the intentions of the proviso in the license that stipulated the training of native Englishmen in the art of cristallo production came to fruition within a few years. The diplomat Sir Jerome Bowes was awarded the Italian's monopoly upon its expiration in 1595 for good service on an envoy to Russia, Although a protracted legal dispute between Bowes and the Verzelini's followed, the Englishman won the suit. By the end of the year, the Crutched Friars glasshouse closed its doors for good.

Tom Roberts