Derived from Old French envoy(e) and designating someone or something ‘sent forth,’ ‘envoy’ and closely related terms such as ‘emissary’ or ‘mediator’ were often used by early modern diplomats and bureaucrats to designate different types of diplomatic agents charged with temporary missions.[1] While appointments of resident ambassadors and the formation of a professional diplomatic corps was gradually adopted across Europe throughout the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there were significant financial costs associated with maintaining a permanent embassy in a foreign court. That, along with reasons of political strategy and symbolic communication, led many polities to preserve some of the ad hoc diplomatic practices that predominated between antiquity and the late fifteenth century. Indeed, the diplomatic terminology inherited from Roman and medieval eras persisted in the designation of temporary agents who were regularly identified with titles such as nuntius, orator, procurator, legatus, or missus.[2] The fact that many of the holders of these titles shared similar functions with resident ambassadors contributed to a terminological confusion which lasted well into the early eighteenth century. François de Callières, the author of the influential De la manière de négocier avec les Souverains (1716), for instance, did not differentiate between envoy and negotiator when describing the function of the ambassador.[3]

In Elizabethan and Stuart diplomatic correspondence, ‘envoy’ and ‘ambassador’ were often interchangeable. The persistence of Latin as a diplomatic lingua franca throughout most of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries favoured the use of terms such as ‘legatus’ or ‘orator’ to identify a series of English diplomatic agents who were appointed to temporary missions. Nonetheless, the English translations of the summaries of diplomatic credentials and letters produced by Elizabethan and Stuart diplomats and bureaucrats frequently resort to the term ‘envoy’. The association between the term ‘envoy’ and the transmission of messages is also attested by references to envoys in the Elizabethan and Jacobean diplomatic correspondence written in English. On 19 February 1569, for example, Christopher Mundt wrote from Cologne to William Cecil that ‘certain great men would wish her Majesty to send an envoy with congratulatory messages, and so to renew the old amity and confederacy with the Protestant princes’..[4] In June 1580, Elizabeth I, hoping to impede the acclamation of Philip II of Spain as king of Portugal, planned to send an unnamed envoy to Lisbon to establish contact with the dukes of Braganza, rival claimants to the Portuguese throne, ‘because we could by no other means, either from their ambassador resident here, or otherwise, understand certainly the state of their affairs, we resolved for our better satisfaction to send an express messenger to them’.[5]The envoy’s role as an extraordinary messenger, as in the instance above, could leave them free to operate in some ways beyond the strictures and formal frameworks of diplomatic hierarchy, largely due to that emphasis on the successful completion of an immediate task – frequently the transmission of crucial information – rather than long-term diplomatic function. Tellingly, this freedom is reflected in the literary form of the ‘envoy’ which English writers began to exploit from the fourteenth century onwards, when it was popularized by medieval authors including Geoffrey Chaucer. It has been well-established that Chaucer and his contemporaries adopted the form of the poetic 'envoi' or 'envoy' from the medieval French tradition of concluding a ballade with a final stanza dedicated to an addressee, often with a moral message. However, in English hands the poetic 'envoy' turned into a significantly more flexible vehicle. In Chaucer's fourteenth-century 'Lenvoy to King Richard', or John Lydgate's moral envoys in The Fall of Princes (1431 – 1448), the traditional humility topos of sending one's text out in the world was combined frequently with messages of instruction, advice, and sometimes sharp critique directed towards aristocratic addressees.

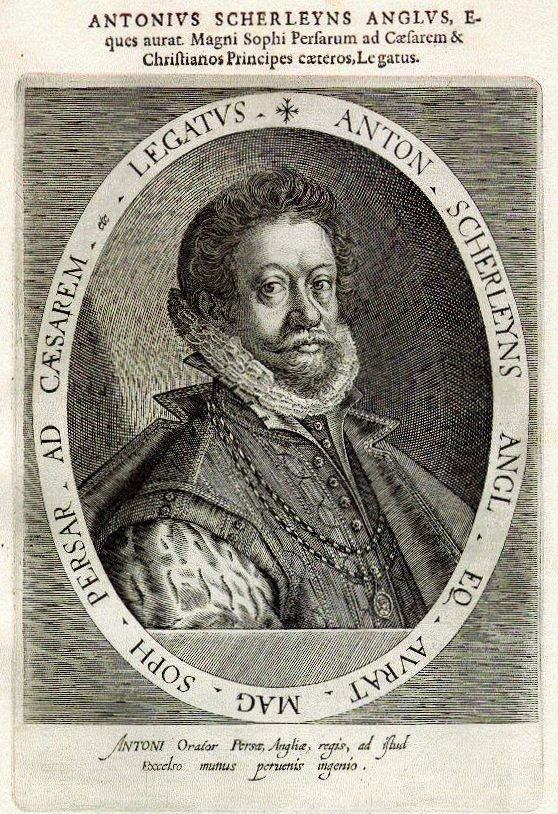

Within actual diplomatic practice, professional contact between states often relied on individuals who were involved in transnational trading and intellectual, religious, or artistic networks. Envoys tended often to be individuals engaged in cross-cultural activities outside diplomacy, such as merchants, clergymen, physicians, travellers, interpreters, or factors. Thanks to their language skills, personal networks, and knowledge of local institutional apparatuses, these individuals were able to carry out specific missions as intermediaries. As a facilitator of communication, envoys were individuals who had or developed the capacity to move between contexts that were both ‘local’ and ‘global’. It was this element of mobility that allowed envoys to further communicate between different political systems and actors.[7] Indeed, Tudor and Stuart monarchs often recruited foreigners as envoys or messengers. Elizabeth I dispatched Matias Becudo, a former Portuguese Franciscan friar, as an envoy to Marrakech to persuade the Moroccan emperor al-Mansur to grant the English a seaport in Morocco thanks to his knowledge of Arabic, Portuguese and Spanish.[8] The Protestant Swiss refugee Stephen Le Sieur, thanks to his knowledge of French and German, was dispatched as envoy or messenger to several diplomatic missions to the German principalities, eventually appointed by James I as resident ambassador to the Holy Roman Empire, Florence, and the German Protestant princedoms, rewarded with naturalization in 1620.[9] In Pocahontas and the English Boys, the scholar Karen Kupperman positioned the Algonquian woman Pocahontas and the English boy-translators in the Chesapeake within this system of official communication, highlighting the role that women and children played within these structures of mediation and negotiation as messengers and valuable linguists.[10]

Foreign diplomatic agents, though not natural subjects of English monarchs, were usually recognized and appreciated as legitimate delegates of the English Crown. The Genoese merchant Horatio Palavicino served Elizabeth I in a variety of special diplomatic missions to Germany and France with the title of ‘envoy from the Queen of England’, and was praised by the Elector of Brandenburg in 1586 as a true representative of Elizabeth’s royal dignity for being able to ‘diligently’ represent ‘her benevolent and favourable good-will’.[11] This acceptance of a foreigner messenger as legitimate representative of an English monarch suggested that, although not vested with the symbolic and political privileges associated with resident ambassadors, envoys and other emissaries could enjoy an honourable status reinforced or made acceptable by the terminological and legal confusion surrounding the definition of different diplomatic posts, even if they were also ‘strangers’ or ‘aliens’ in the eyes of the law. In 1688, the author John Northleigh did not make a clear distinction between the functions of ‘ambassador’ and ‘envoy’, arguing that the ‘Character of an Envoy is the most immediate representation of the King, and every Act of his, but another of the State’.[12]

However, by the end of the seventeenth century, the employment of foreigners as diplomatic agents became more problematic. The development of a professional diplomatic corps, and the sensitivity of the subjects dealt with by diplomats, encouraged the perception that diplomatic service should be an exclusive of English nationals. The ascension of William of Orange to the English throne and apprehension of growing Dutch influence on the English state led to fear that the king could ‘appoint a Dutch Man Ambassador or Envoy to any Court in Europe’ since this would lead to ‘Sacrificing the Concernments of England, in that Court and Country, to the Pleasure and Profit of the Hollanders'.[13]

Although women tended to be theoretically excluded from formal diplomatic structures, ambassadresses, female courtiers, servants and other women who had privileged access to relevant political actors were often employed as informal envoys or messengers. Elizabeth I commissioned Lady Mary Sidney, for example, to discreetly establish contacts with the Spanish ambassador, Álvaro de la Quadra, regarding a potential marriage with Archduke Karl of Austria.[14] Wives of English ambassadors stationed in Istanbul were often employed as discreet envoys to the seraglio as part of a strategy that sought to circumvent the restrictions imposed to male political agents to access a key space of Ottoman courtly politics. Katherine Trumbull, the wife of William Trumbull, the English ambassador to the Sublime Porte between 1687 and 1691, befriended Sultana Ümmühan, the aunt of Sultan Mehmed IV. This relationship allowed the ambassador, through his wife, to explore a new and privileged channel of communication with the Ottoman court.[15]

With the rising commercial interests of the English throughout the seventeenth century, the term ‘envoy’ was frequently applied to diplomatic agents of non-European polities. The English East India Company (EIC) and the Levant Company encountered polities with highly-developed diplomatic systems with their own complex protocols, practices, and conceptual frameworks. While European ambassadors and envoys enjoyed a privileged status inspired by the Roman law of nations, in the Ottoman Empire, Morocco, Savafid Persia or Mughal India, English and other European diplomatic agents found different notions of ambassadorship predominated.[16] These often granted a limited legal and political status to diplomats. n his account of his travels to Persia and India, John Chardin explained to his readers that ‘the Persians make no distinctions between Embassadours, Envoys, Agents, Residents, &c. but still make use of the word Heltchi, which comprehends all’.[17] The encounter with diplomatic systems based on different notions of ambassadorship, which often required an almost ongoing negotiation with local authorities on the status of English diplomats, generated tension and contributed to a negative depiction of polities outside Europe by the English. Sir Thomas Roe, for example, complained that the Mughal court was a place ‘not fit to keep an Ambassador’ and depicted Mughal diplomatic practices as ‘affronts and slavish costumes’.[18]

Challenged with different categories of diplomatic agents and with a preference for temporary missions, the English and their European rivals in Asia and Africa frequently used the term ‘envoy’ as the closest embodiment of the Persian heltchi mentioned by Chardin. John Ovington observed ‘a Chinese Madarine, who arrived at Suratt in the quality of an Envoy from Limpo’, and Francis Brook transcribed a proclamation signed by William and Mary on an ‘[o]ffer from the Emperor of Fez and Morocco, by his Envoy sent hither to Treat about a general Redemption of all the English that are his Slaves’.[19] As the scholar Jonathan Burton observes, the ‘failure to consider how notions of an embassy or an ambassador can be specific to particular cultures’ often led to an undervaluation of the diplomatic initiative for non-European polities.[20] The widespread use of the term ‘envoy’, particularly in relation to African or Asian diplomats, suggests a reduction or over-simplification of these societies and their own political and intellectual systems.