A common figure in early modern life, the ‘rogue’ was part of a negatively perceived, transient group of people that also contained vagrants and vagabonds. Its etymological origins, perhaps appropriately, are unknown, but the term developed during a period when the government was increasingly concerned with issues of population movement and ‘[m]asterles Men’, particularly after the Reformation, as Tudor monarchs from the mid-sixteenth-century increasingly sought to consolidate their power within the realm.[1] Thomas Harman, who also wrote about Gypsies, was one of the first writers to use the term ‘rogue’.[2] According to Harman’s definition, there were two types, one made and one born. A born rogue, according to Harman, was a ‘[w]ylde Roge’ who had been ‘begotten in barne or bushes’ and was ‘from his infancy traded up in treachery’.[3] This type of rogue had been referenced in John Awdelay’s The fraternitye of vacabondes (1561), where he described them as having ‘no abiding place but by his coulour of going abrode to beg’ and stated that all who do this ‘be properly called Roges’.[4] Unlike a ‘wylde Roge’, the ‘rogue made’ was Harman’s innovation. A rogue of this kind was ‘neither so stoute or hardy as the uprightman’ and despite possibly having to learn this trade there was ‘nothing to them inferiour in all kynde of knavery’.[5] In the seventeenth century, John Cowell built upon Harman’s definition to include poor travellers as ‘counterfeit rogues’, describing the ‘Roag’ as an ‘idle sturdie beggar...wandring from place to place without passport’.[6] The rapid development of the term ‘rogue’ during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries was therefore matched by legal and governmental attempts to define, legislate, and restrict the lives and mobility of those considered to be outside the reach of English authorities and policy-makers.

Elizabeth I’s parliaments attempted to restrict the movement of people and labour to prevent unregulated mobility. The Act for the Relief of the Poor (1563) and the Statute of Artificers (1563) were attempts to prevent the growth of transient people by regulating the movement of people and labour, and it is telling that these were created around the same time as ‘rogue’ appeared in popular print.[7] The 1572 Act for Punishment of Vagabonds, known for reducing the severity of punishments for wandering players, introduced much harsher punishments for traditional ‘rogues’. According to the act, those ‘Rogues shall appeare to bee dangerous’ and who refused to ‘be reformed of their rogish kind of life’ would not only risk a jail sentence but also, for the first time, could be punished with transportation or impressment ‘perpetually to the Galleis of this Realme’.[8] The Act also accounted for foreign rogues, ordering that the ‘Scottish, or Irish Rogue’ be sent back to the parish or port that they entered from and ‘be transported at the common charge of the Countrey where they were set on land’.[9] It also became increasingly important to ensure that these laws were enforced, empowering ‘Churchwardens and overseers’ to punish rogues and answering public complaints that constables had ‘in many places in suffering Rogues to wander & beg in the streetes’.[10] Furthermore, the act also ordered that those constables who were found to be ‘negligent, or remisse in the execution of the statute’ were to be punished ‘so farre as the law and authority of the chiefe Magistrate in that place will allow’.[11] In London, the officers of the cities were given the authority to ‘apprehend Rogues and to punish them’ in twice weekly patrols of the streets within their jurisdictions.[12] The fixation on trying to resolve the issue of transient people continued into the eighteenth century, with proposals for finding employment for the poor that would keep ‘all Rogues...kept and set to Work’.[13] After the Restoration, Parliament passed an act in which local constables of towns and cities were to apprehend ‘rogues’ found begging or wandering and to punish them severely.[14]

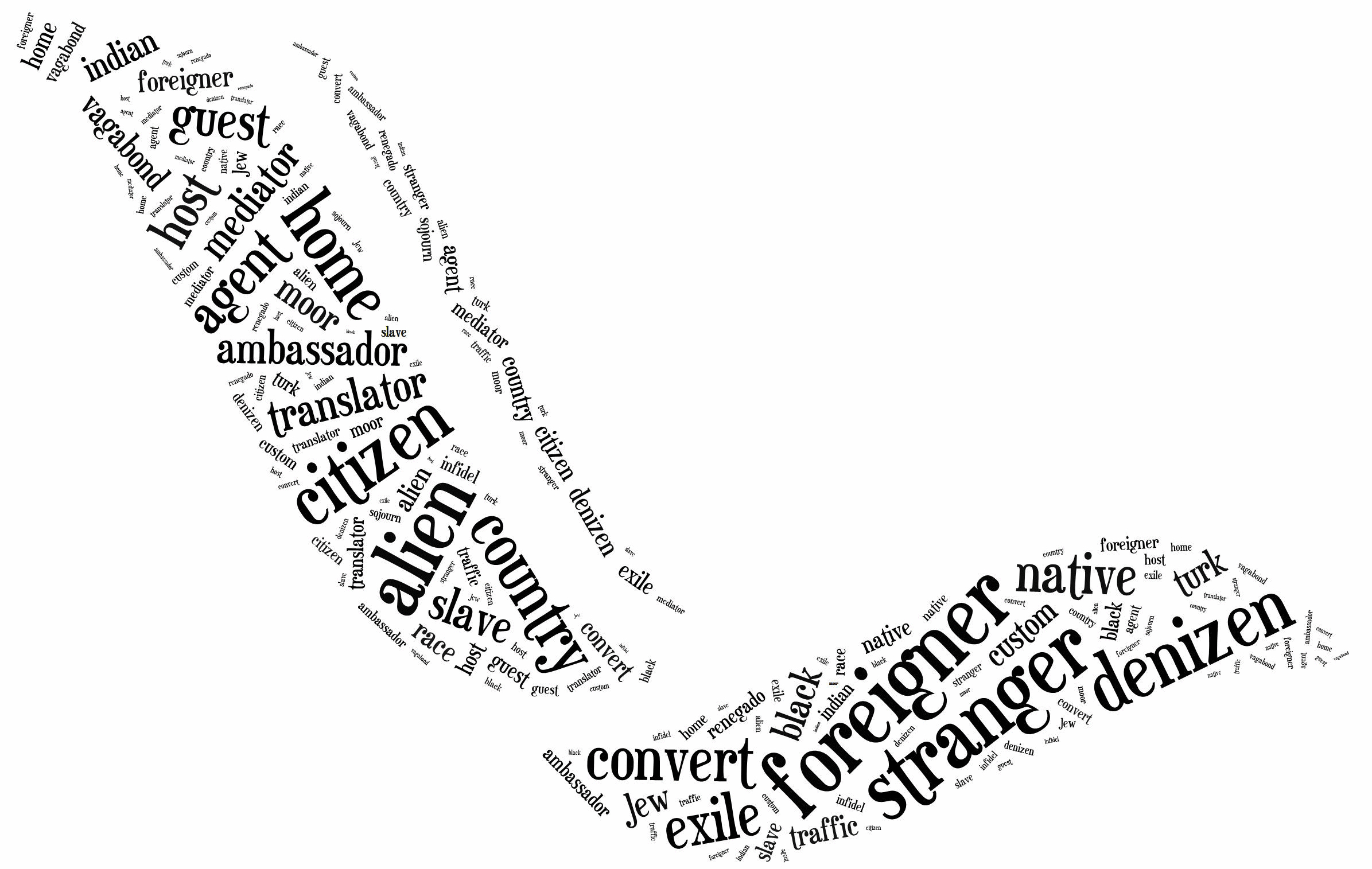

The marginality and placelessness of figures that authorities identified as rogues, ‘uprightmen’, ‘cony-catchers’, or vagabonds, meant that the terms were invariably inflected by social status. Patricia Fumerton has pointed out that the sense of estrangement that was associated with vagrants and rogues 'can be seen metonymically to embrace most of the lower orders, not just the indigent and homeless, of early modern England: itinerant laborers, including servants and apprentices, as well as those poor householders from the lowest depths of the amorphous "middling sort," who were at any time liable to such unsettling change'.[15] When Shakespeare’s Hamlet calls himself a ‘rogue and peasant slave’ (II.ii), the association between poverty and being a rogue would have been commonplace. Despite the reality of isolation and insecurity, placelessness was frequently transformed into visions of rogues and vagrants as virtual ‘strangers’, representatives of an alternative social order operating simultaneously and beneath the state’s government. As Nandini Das has shown, the fundamental premise underlying Robert Greene’s hugely popular cony-catching pamphlets of the early 1590s, for instance, is the existence of a sprawling criminal underworld inhabited and governed by these marginal figures, with their own rules, laws, and vocabulary (‘canting tongue’). Greene’s A Notable Discovery of Cosenage (1591) ‘presents the English reader with an unavoidable image of himself as a traveller and a stranger in his own land, and offers Greene’s “R.G.” as his only guide’.[16] At the same time, that alterity is also exploited by Greene and contemporaries like Thomas Dekker, whose pamphlets The Bellman of London (1608) and plays like The Roaring Girl (1611) featured male and female cozenors with strong independent spirits. In such texts the ‘rogue’ becomes the stranger at home, whose perspective throws a raking light across familiar social practice and norms.

Throughout the seventeenth century, Parliament continued to punish and restrict those they called rogues. In 1603, Parliament reintroduced the act of branding rogues with an ‘R’ the size of a shilling, with the punishment for repeat offences increased to death without benefit of clergy.[17] Within six months of ascending to the English throne, James I issued a proclamation to combat the threat of ‘Rogues’ who had ‘grow[en] againe and increase to bee incorrigible, and dangerous’.[18] In 1621, a draft bill in Parliament, though never passed, explicitly sought to subject ‘wandering rogues’ to extremely harsh conditions that amounted almost to slavery.[19] Increasingly too, English authorities used deportation as a solution. An Order of the Privy Council detailed specific nations and geographies where rogues could be deported to, which included ‘the New-found Land, the East and West Indies, France, Germanie, Spaine, and the Low-countries, or any of them’.[20] In 1609, the Lord Mayor of London attempted to establish a fund to remove the city’s idle poor to Virginia, acquiring financial help from the livery companies to do so.[21] Although the scheme did not succeed, deportation to America and the Caribbean became increasingly popular in the seventeenth century, considered to be a solution to both a domestic problem while addressing the underpopulation in England’s fledgling colonies, where death rates during particularly harsh winters could reach ninety per cent. By the later seventeenth century, indentured servants and transported felons make appearances in popular English literature. In Aphra Behn’s play, The Widow Ranter, or, The History of Bacon in Virginia (1690), a newly arrived indentured servant in the colony humorously fails to understand colonial English, rich in underworld slang. ‘You Rogue’, Widow Ranter says, ‘’tis what we transport from England first’.[22] The mobility of ‘rogues’, and the difficulty of ‘placing’ them, made such individuals a focal point for intense debate about state regulation and visions of empire. While some MPs, like the Jacobean Edwin Sandys, saw the sending of ‘rogues’ to the colonies as a method that stabilized the colonies and solved domestic social ills, not all policy-makers advocated transportation. Francis Bacon believed it was a ‘Shamefull and Unblessed Thing’ to transport ‘the Scumme of People, and Wicked Condemned Men’ to found American settlements.[23] Bacon warned that ‘they will ever live like Rogues’, for ‘rogues’ would ‘not fall to worke, but be Lazie, and doe Mischiefe, and spend Victuals, and be quickly weary’.[24]

During the civil wars, the term ‘rogue’ was used widely in the political pamphlets of either side, but particularly in Royalist literature, to describe those who supported and fought for Parliament. The term became synonymous with ‘rebel’, regularly used by royalist forces to highlight what they believed to be the treacherous behaviour of their enemies, or as the royalist commander the Earl of Northampton described them, ‘base rogues & Rebels’.[25] Royalists often banded Parliamentary forces – ‘roundheads’ – with ‘rogue’: ‘Rogues and Round heads’, ‘you Roundheaded Rogues’, ‘these Roundheadly Rogues’.[26] As the staunch royalist Walter Balcanquall wrote from Scotland, that was ‘no better names then Rogues’ for the ‘offenders in the first uproare’ against the Crown.[27] In America, support for Parliament was lukewarm and came mostly from the settlers of Massachusetts Bay. After the restoration of the monarchy in 1660, many parliamentary supporters resettled in Massachusetts, prompting one Church of England minister to claim that the ‘Governor of Boston’ was a ‘Rogue’, leading a colony full of ‘[t]raitors & Rebels against the King’.[28]

When used in the colonies, the term ‘rogue’ retained similar connotations to the term in England, signalling idle wanderers or journeymen, while interactions with foreign peoples, cultures, and faiths across the globe imbued the term with a wider range of usages and meanings. Territorial and commercial expansion increased opportunities for English men and women to encounter, and even transform into, another type of rogue: the apostate. Alongside commercial and diplomatic interactions with India, the Levant, North Africa and Persia, religious exchanges with numerous faiths were an everyday part of life abroad. Rogue apostates not only highlighted the danger to the nation of cultural exposure abroad, but also presented a danger for the future reputation of the nation if they gave sway so easily. One example was in Constantinople in 1650, where the Levant Company reported that a man who had refused to convert to Islam whilst in captivity, did so upon his release at the persuasion of yet another unnamed English apostate, before he disappeared from the English records all together.[29] The consul at Tripoli, Thomas Baker, described one Englishman who converted to Islam and, having been ‘admitted into that accursed Superstition’, was ‘secured’ aboard a ship before the end of the day, ‘like a Rogue’.[30] It was not just conversion to Islam or Hinduism that the East India and Levant companies guarded against, but to Catholicism as well. In 1648, one of the factors at Fort St. George in Madras reported to the EIC that the grandson of the fort’s founder had ‘turn’d Papist rogue’ and fled to Sȁo Tomé.[31]

The religious apostate, much like the anti-royalist rogue or the ‘self-made rogue’, was an individual whom others perceived as having deliberately abandoned part of his or her national allegiances. Rogues were consistently viewed as treacherous and operating in a state of ‘doubleness’, willfully subverting English structures of governance and belief.[32] On the stage, rogues were double-dealing characters, morally suspect and ferociously independent, often promoting their own interests at the expense of the common good. Meanwhile, the ‘undeserving poor’ were categorized as rogues and ruthlessly punished through English law. Whether travelling along the waterways of the Chesapeake or the fields of Shropshire, the ‘rogue’ was always believed to operate outside national interests.