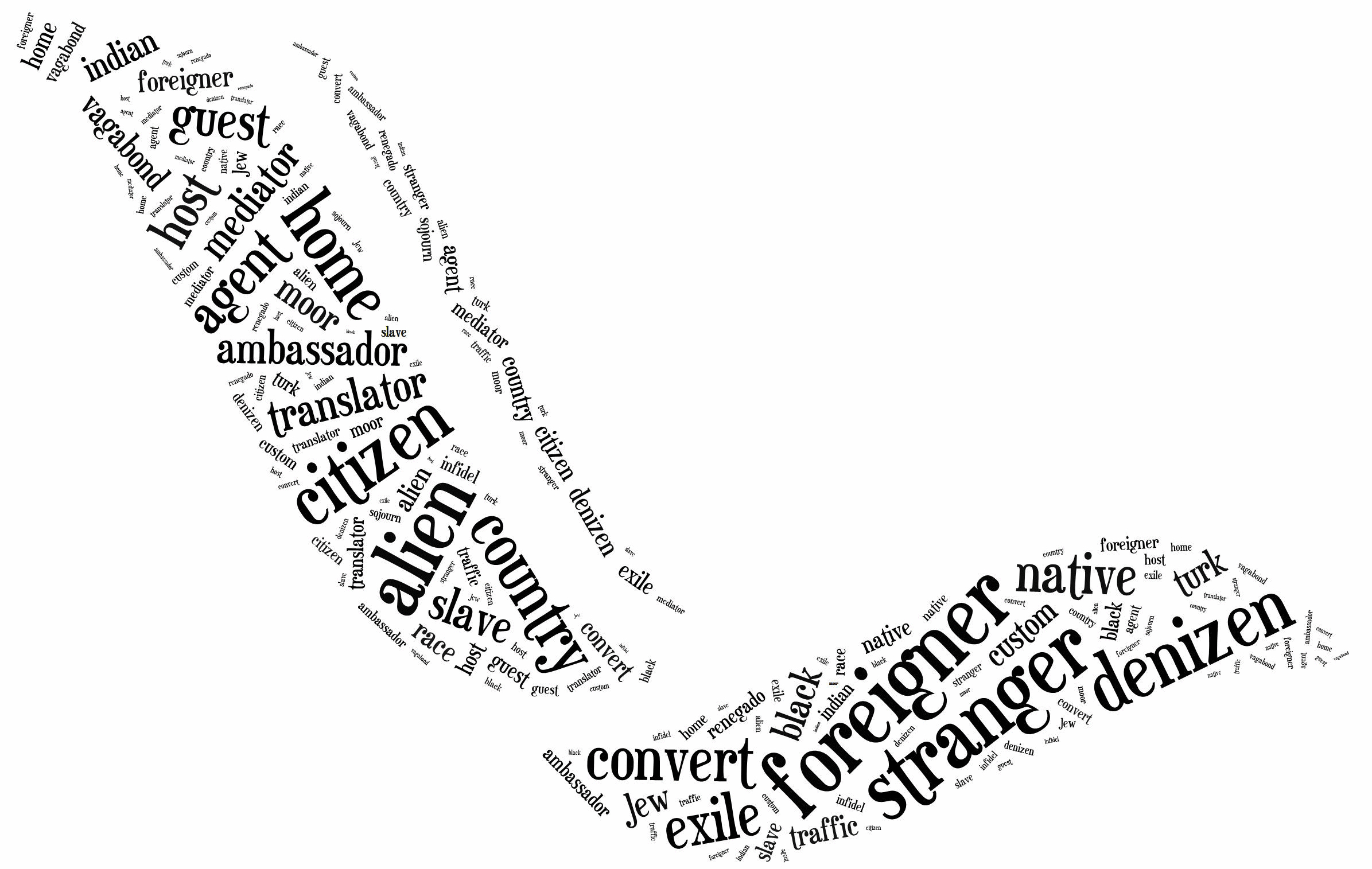

Firmly entrenched within the language of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century imperialism, it is difficult to dissect English usages of the term ‘settler’ in an era when England’s colonial endeavours were emerging. By the 1680s, a ‘settler’ had become an individual commonly associated with England’s increasingly global territorial and commercial ambitions, but the term was previously used more generally to denote someone who fixed or established order.[1] The term therefore carried a sense of ‘doing’, of an identity rooted in profession or service. ‘Settler’ first appears in foreign language manuals published at the end of the sixteenth century. The second generation Italian migrant, John Florio, uses the term in 1598 to describe a hairdresser (acconciatore) as a ‘mender, a settler, an order’.[2] Just over a decade later, in A dictionarie of the French and English tongues, Randle Cotgrave described ‘a Ficheur’ as a ‘fixer, fastener, settler, or setter’.[3] The most common domestic use of the term was within religious and political language, identifying an individual or group who had established, settled, or planted varying forms of religions and governments. This meant that early modern English people recognized different individuals and groups as being settlers.

The most common domestic use of ‘settler’ in the early seventeenth century was what is often termed as the ‘settling’ or founding of Protestant religious authority. Protestants and Catholics identified Martin Luther, for instance, as a ‘settler’ in later discourses. Richard Smith, the Catholic chaplain to Viscountess Montague, described Luther as the ‘settler of the Protestant Church’.[4] Some years later, Smith again described Luther as a settler, calling him the ‘renewer, the Founder, the Restorer, the settler and promulgator of [the Protestant] Church and Religion’.[5] Smith had lived in Europe as a student and teacher at the English colleges in Rome and Seville during the height of the Counter-Reformation, and he hardly viewed Luther’s role as a settler of religion as positive: Luther was a ‘[s]ettler of a thing corrupted’.[6]

In short, ‘settler’ developed out of increased mobility, becoming linked to individuals and religious communities who were forced to settle new communities as a result of confession, dispute and the subsequent threats posed to their lives and livelihoods. Much like those who considered Luther the founding settler of the Protestant faith, many English migrants who established exile churches in Europe were considered settlers. The Catholic Smiths eventually settled in an English college in Paris and lived in the household of Cardinal Richelieu. Francisco de Peralta, the Spanish rector of the English Jesuit College of Seville where Smith had taught, described a group of English prisoners in Spain in the manner of settlers. These men had been converted to Catholicism by the English Jesuit Robert Persons: ‘[s]ome of the men settled here, while others took service on the King’s service as sailors or soldiers’ (‘se quedaron a vivir por aca, otros sirviendo al Rey en las galeras por marineros y soldados’).[7] Religious migrants who moved across the Channel to settle homes and churches in England were also identified as settlers. In 1636, the Archbishop of York wrote to William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury, of the growing number of Dutch and French settlers in Lincoln, noting that amongst them was a minister called Cosellys who was the ‘principal settler’ of the church there.[8]

Alongside the practical acts of establishing or settling churches, English authors also discussed religion in terms of it being a settler of peace and stability across society, from the individual to the nation. The Calvinist cleric, Thomas Taylor, wrote of the role of religion and godly meditation in settling a peaceable domestic life, particularly for women, in his Commentarie upon the Epistle of S. Paul written to Titus (1612). Taylor was particularly concerned with the role of religious observation as a ‘setler of the comfort of her life’ as it ‘suffered not undutifulness to the husband, unnaturalness towards the children, unmercifulness towards servants’ and ‘untowardness in her own duties’.[9] On a national level, the dutiful observance of religion was also seen as a key means of ensuring peace, stability, and loyalty to the government. As the poet Francis Quarles wrote, ‘true Religion is a settler in a State’, confirming ‘an established Government’.[10]

Second to the religious identity of domestic settlers were those involved in the establishment of political and governmental authority in England. In the years surrounding the English civil wars, individuals and groups on both sides of the political divide were accused of encouraging instability by settling various forms of government. Linked to the religious use of the term, the ‘settler’ in the context of the political conflicts of the mid-seventeenth-century was someone who could be perceived as both positively or negatively establishing a form of political order. In 1647, one author pointed out the irony of claims that the army in its ‘preparations for war’ was seen as being ‘settlers of a happy Peace in England’, since those who ‘strive to settle Peace by the sword, distract it’.[11] Following the return of Charles II from exile in Europe and the Restoration of the Crown in 1660, many who were wary of the turmoil and memory of the civil wars and Interregnum were keen to remind Charles of his responsibility as a settler of good government. The king was charged with establishing order as a ‘settler of outward peace’.[12] Like those who would venture abroad establishing English colonies in the Atlantic, Charles was seen as a ‘[s]ettler and Establisher’ whose movement and relocation would ensure that good English government was established and maintained, both in England and abroad.[13]

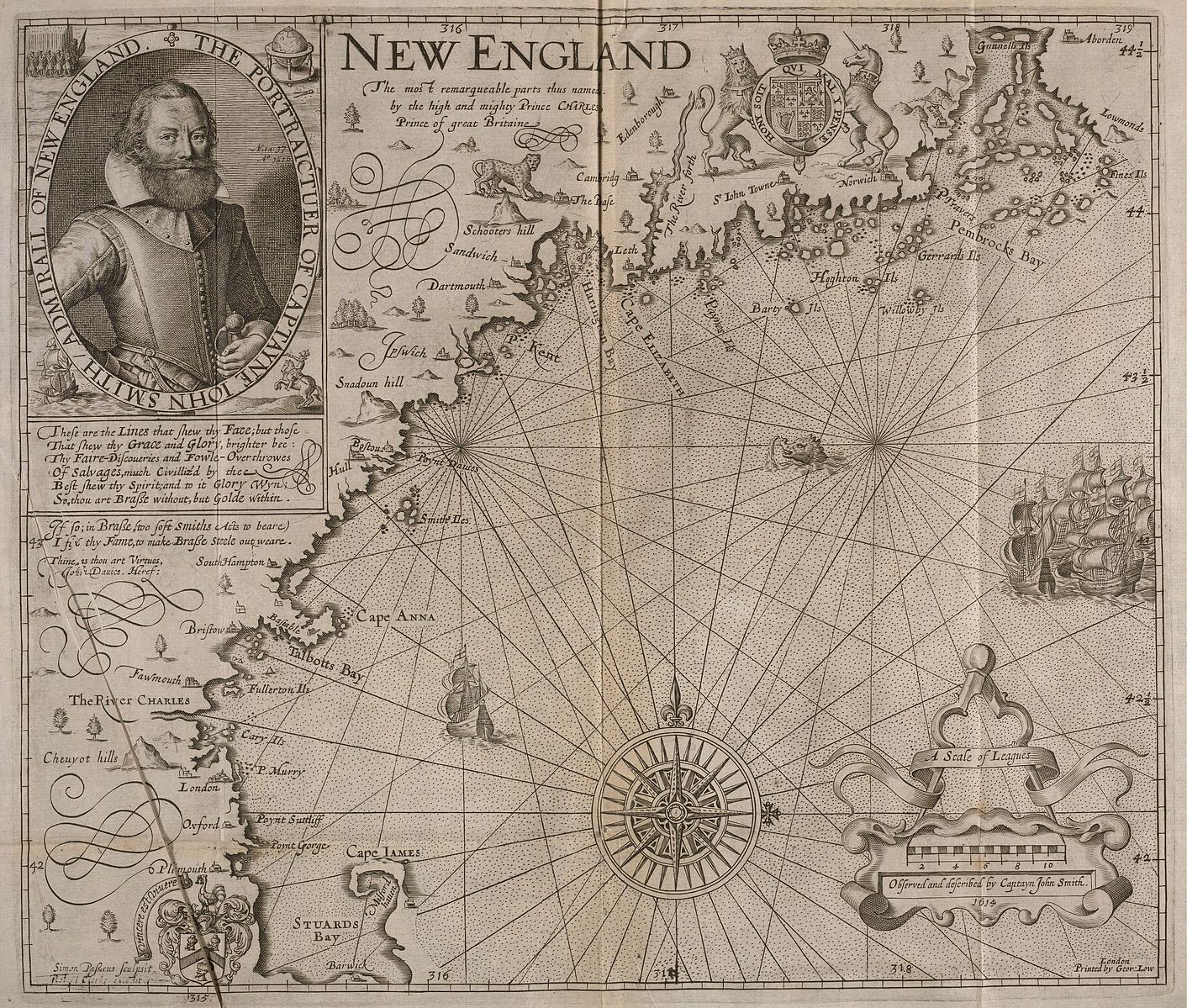

As English territorial and commercial endeavours expanded abroad, so too did attempts to establish and settle English authority upon peoples and geographies across the globe. Although the term is absent from colonial charters, those who ventured to America and the Caribbean were seen to be migrating to ‘settle themselves, dwell and inhabit’ specific places.[14] This more established view of the ‘settler’ as colonist and migrant took shape in the years following the Restoration. Chief Justice John Vaughan advanced more nuanced legal definitions of settlers and their rights in the 1670s.[15] In ensuing legal cases, common law for settlers ‘twas their birthright’ and upon all ‘uninhabited country, newly found out by English subjects, all laws in force in England are in force’.[16] The term ‘uninhabited’ referred to land not belonging to English or European powers, where the legal rights extended to settlers either ignored or did not take into account pre-existing indigenous communities. Granting rights and privileges for English men and women to ‘settle’ therefore legitimized a process that allowed the English to subjugate or drive out Native Americans and other indigenous groups – settler colonialism.

The role of ‘settlers’, therefore, became increasingly associated with the mechanisms of expansion and the establishment of various forms of trade and trading outposts. The member of Parliament, merchant, and Guinea Company investor Nicholas Crisp was one of the first men to use ‘settler’ in relation to trade, and he did so specifically in the context of the slave trade on the West Coast of Africa. In a petition to Parliament in 1660, Crisp pleaded he be granted £20,000 in funds lost to trade, which would help to pay for his release from prison.[17] Crisp believed that amount was long due in recognition of his ‘merit from his Nation’, since he had been the ‘first Discover and Settler of that Trade’ to Africa.[18]

In England, the landed elite had long built their authority around lineage and a sense of permanence, their power strengthened by their claims to settling land and on a juxtaposition against tradesmen, journeymen, and agricultural workers who were often forced to move from county to county seeking work.[19] The deportation of Africans to English plantations, and the dispossession of indigenous groups of their lands, wove more racialized ideas of dominance within the term. A clear separation emerged between industrious ‘settlers’ and enslaved Africans. It pinpoints a moment of change, whereby the term ‘settler’, when applied in the context of plantation, merged domestic ideas of establishing peace and stability with colonial attempts to ‘civilize’ other territories and its peoples. Increasingly, the English believed that to ‘settle’ was not just to cultivate other geographies, but to dominate non-English peoples. In 1682, nearly twenty years after Charles II had reissued the Carolina Charter, one pamphlet celebrated the ‘pleasant Pastures, and shady Savana’s [sic]’ that could ‘most generously refresh the Settlers’, with an abundance of natural resources ‘to compensate the modest Care, and Industry of the Settler’.[20] It was through the ‘industrious Settlers, and Planters’ that Carolina had been able to ‘prosper very well’.[21] Yet the success of these settlers hinged on the work of African slaves, ‘whose labour proclaims the Settlers plenty’.[22]

By the end of the seventeenth century, the identity of the ‘settler’ had been transformed. While men and women from across the globe settled in new spaces, ‘settler’ as a noun in English usage referred most frequently to white men as heads of household. Women continued to be associated with earlier ideas of settling – Elizabeth ‘settling’ the Protestant religion for example – but taken abroad, the domestic concepts about orthodoxy and governance that surrounded ‘settlers’ were adapted and mutated into its more commonly-associated colonial meaning.[23] By the end of the century, authors recalled how many ‘[p]roprietorships’ had been ‘granted to the Settlers of Colonies in America’ over the century, whilst others sought to ‘encourage new Settlers’ to travel abroad.[24] Much like their domestic counterparts, the responsibility of these English settlers was to establish and ensure the stability and security of English governmental authority. However, unlike in England, the colonial settlers also sought to extend this authority beyond the traditional boundaries of English control. In doing so, the colonial experience mutated the identity of the settlers from the protector of authority to the embodiment of authority.