Image by Lauren Working

I recently returned from a warm and fruitful summer at the Huntington Library in California. As a short-term research fellow, I went to explore how English attempts to ‘civilise’ other peoples in the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras informed the way writers and policy-makers articulated their own civility and conceived of their political responsibilities, at a time when the success of English colonisation was by no means secure.

The first age of expansion exposed English men and women to diverse cultures, but it also forced the English to see their own values in relation to the peoples they encountered. A strange mix of curiosity and disdain, vulnerability and superiority mark many speeches, plays, and political discourses from this time. The Scottish king James VI’s ascension to the English throne in 1603 created intense, often xenophobic concerns over the influx of Scots in England, for example. Libels and satires mocked the king’s Scottish entourage at court, and in Calvin’s Case (1608), the highest justices of the realm debated whether the king’s Scottish subjects were entitled to English privileges, such as land-holding in England, or whether they remained legal ‘aliens’. Debates over how to categorise or assimilate foreigners were accompanied by images that perpetuated assumptions about the perceived inferiority of those beyond England, whether in the Highlands or in America:

Huntington Library MSS: HM 25863, f. 28r.

Image by Lauren Working.

Authorities in Protestant England attempted to enforce strict codes of personal behaviour as a means of social control: civility became an important component to creating a godly, obedient society, and intercultural encounters played a role in how these manners were articulated. Moral literature probed the tensions between virtue and travel, between the exoticism of other cultures and fears of internal corruption. At the Huntington, I found that conduct books, with their discussions over the rising fashion for tobacco smoking, provided rich sources for thinking about the influence of intercultural exchange on the social lives of London gentlemen.

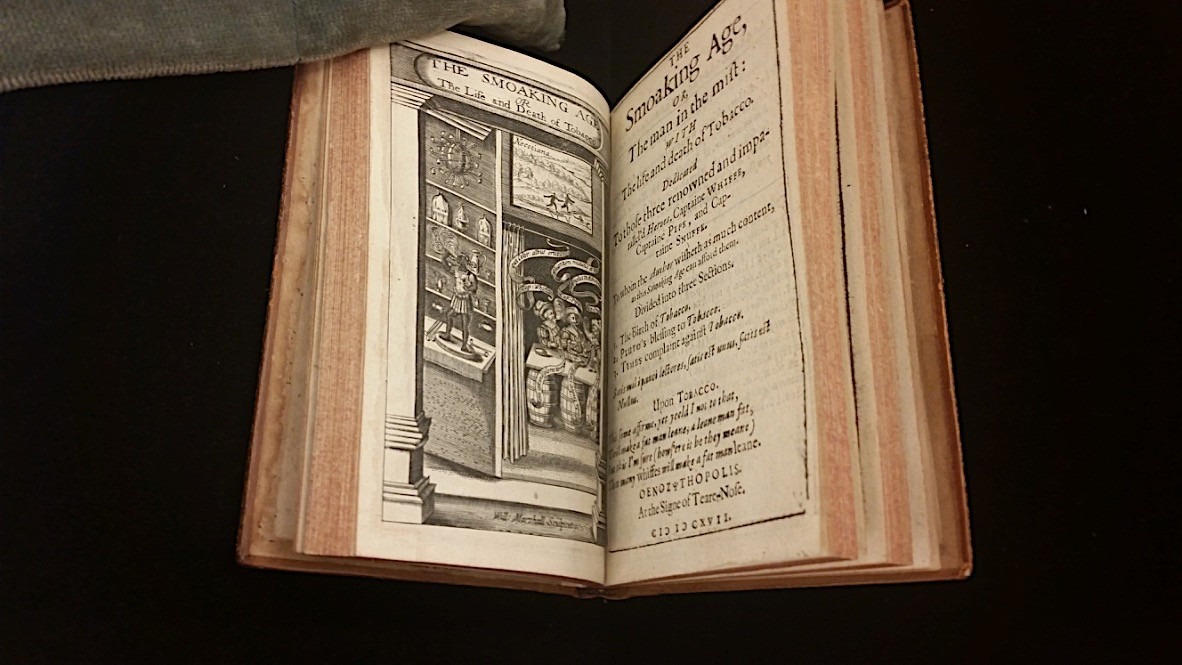

In 1617, Richard Brathwaite translated a humorous Continental drinking manual into English, adding a unique component of his own. Dedicating half the text to the subject of tobacco, Brathwaite framed the urbane gentleman as one informed by, and invested in, the world beyond him. The text mentioned Africans and Bermuda, Ireland and navigation. It also expressed an awareness of status – not just between Englishmen and non-Englishmen, but between the elite and non-elite. Projecting stylish gentlemen as witty versifiers and frequenters of tobacco houses, juxtaposed against the ‘common sort’ who visited alehouses and who failed to follow the carefully-prescribed rituals of gentlemanly social interaction, Brathwaite’s text insinuated that members of the ruling elite were those who possessed the necessary civility and political acumen to successfully oversee colonization: that even the potentially destabilising influence of an indigenous commodity like tobacco might be artfully incorporated into the rites of sociability and informed discourse.

Huntington Library, 60460.

Image by Lauren Working.

Early colonial texts and maps are among the many celebrated collections at the Huntington, but its costume books and conduct literature offer some clues as to how the ideas behind empire and state were conceived and enacted – not beyond the realm, but within it. As TIDE aims to investigate in coming months, the intermingling of cultures shaped domestic institutions, discourses, and narratives through relationships and processes that must be approached beyond oppositional terms like ‘self’ and ‘other’, or ‘European’ and ‘native’, to those in between.