What is #Gateofaccess?

‘Any object, intensely regarded,’ observes Buck Mulligan in James Joyce’s Ulysses, ‘may be a gate of access to the incorruptible eon of the gods’.

We’ll leave presumptions about the eon of the gods to neoplatonists, but we at TIDE thought ‘gate of access’ aptly conveyed the importance of objects in engaging with the past, and, with it, the human condition. The term evokes the potency of objects and texts as artefacts, which transport us beyond what we think we know and push us to new knowledge.

In light of this, we’ve designed our new Twitter hashtag, #Gateofaccess, to focus on objects from English collections that enrichen our understanding of transcultural exchange in the early modern period. A sixteenth-century glove, for example, worn by an Englishman but stitched with Venetian silk using Indian chintzes, indicates the influence of other cultures on consumerism and taste in Elizabethan England. Africans in Stuart portraiture, or English governors or ambassadors depicted wearing Native American or Persian accessories, might be used to raise questions over ethnic difference and social status. How, we might then ask, do these examples of cultural hybridity complicate the anxieties about foreign influx and influence so often depicted in printed works?

One day a week, in series that last four to six weeks, our Twitter account, @ERC_TIDE, will exhibit objects in partnership with a particular museum or collection. Working closely with curators and archivists, these tweets will showcase objects of transculturality while highlighting the archives belonging to a range of local and national galleries and libraries. By working with various cultural institutions and research departments, #Gateofaccess will explore how objects can help foster a dialogue about the past, while encouraging more people to engage with their history through art and cultural institutions.

Our first showcase: tobacco and global competition

Our first #Gateofaccess is a collaboration between TIDE, Liverpool Special Collections and Archives, and the National Pipe Archive. Thanks to the robust efforts of John Fraser (1836 – 1902), secretary of printing and publishing for Cope’s Tobacco Company in nineteenth-century Liverpool, the university owns an abundance of early modern tobacco treatises and pamphlets. Beyond printed works, the National Pipe Archive houses their vast collections of pipes, tins, jars, and related objects, at the University of Liverpool’s Department of Archaeology.

These objects reveal the transcultural elements inherent in sixteenth and seventeenth-century debates about health, morality, imperialism, and pleasure. Mingling concerns over global competition, religious orthodoxy, and a fierce sense of national pride, tobacco became a battle ground over which English anxieties over identity were fought.

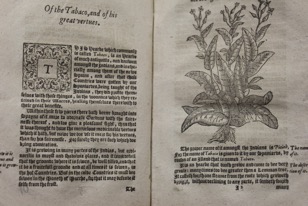

Medicinal texts like John Frampton’s translation of Nicolas Monardes’ Joyfull newes out of a new-found world (1596) explored fundamental questions about the properties and effects of tobacco. Did tobacco ‘corrupt’ the body? If it was indeed ‘healthful’, as some doctors claimed, did it corrupt the soul? A copy of Monardes’ Joyfull newes in Special Collections here at Liverpool indicates that the owner of the treatise actively used the book to solicit medical advice. The marginalia notes the cures that American commodities might provide for such ailments as the ‘gut & sweat’. Treatises about tobacco highlight both texts as objects, passed around and annotated, and illustrate the transculturality of tobacco debates: Englishmen were reading texts written by the Spanish and French, about a plant cultivated in America and smoked by ‘pagans’.

As for the pipes themselves, they show us that beyond written debates about medicine and the ethics of smoking, the material object influenced English social rituals and reflected the successes of imperialism through the booming tobacco trade. Pipes with the smallest bowls were made in the early seventeenth century, while the larger pipes indicate the availability and low cost of tobacco by the later seventeenth century, as English tobacco exports from the colonies escalated. The historian Edmund Morgan went so far as to liken the Virginia of the 1620s to the rough frontier towns of the Klondike during the 1890s gold rush, a ramshackle world where merchants, labourers, and surveyors arrived with dreams of striking rich.

The colour of the clay, too, tells a story of cultural difference. While keeping the overall form of the bowl and stem, the English rejected pipes modelled on those of the Algonquians who taught them to cultivate the plant in North America. Rather, pipes in England, from the earliest examples, were made of the whitest possible clay, eschewing overt associations with Native American ritual. Of the thousands of tobacco pipe fragments that survive, there is no evidence of a single example of a Native American pipe, characterised by darker clay and thicker, larger bowls. The absence of evidence in the archive can be as indicative as what is included in it.

Our #Gateofaccess series launches on Twitter this week @ERC_TIDE. Don’t hesitate to contact the project’s public engagement coordinator, Dr Lauren Working (l.working@liverpool.ac.uk), to discuss #Gateofaccess collaborations in more detail.

Lauren Working