Those who visit the Saint Roch Church in Lisbon would probably pay more attention to the extravagant baroque chapel of St. John the Baptist, than to the little tomb of an Englishman who died in 1608 named Francis Tregian. Some four hundred years ago, the resting place of the first Catholic recusant to lose his entire estate under Queen Elizabeth attracted several visitors who hoped to be blessed by a man who died in the odour of sanctity.

Tregian was one of the wealthiest men of sixteenth century Cornwall, with an estimated estate worth three thousand pound, a considerable amount for the period. His wealth and support to persecuted recusants made him an obvious target during the Elizabethan repression of Catholics. On the night of 8 June 1577, Tregian was arrested for lodging Cutberth Mayne, an English missionary from Douai accused by the Elizabethan authorities as a Papal agent sent to prepare a rebellion against the Queen. However, Tregian’s biographer, probably inspired by the growing reputation of Elizabeth as a depraved woman across Catholic Europe, suggested that real motive behind his arrest was his refusal to the Queen’s improper advances.

Doubts surrounding Tregian’s trial forced the initial death sentence to be remitted to life imprisonment and the definitive confiscation of his estate. After almost twenty-eight years as an itinerant prisoner, Tregian was released by James I in 1606 and permanently banished.

Like many Catholic exiles, Tregian’s first stop was Douai. He then travelled to Madrid where he was received by Philip III, who granted him a life pension for his staunch defence of Catholicism against Elizabethan heresy and repression. After receiving his pension, Tregian settled in Lisbon with his family.

The Portuguese capital, then under Spanish Habsburg rule, was one of the main destinations for Catholics fleeing England. The city was easily accessible from the north Atlantic and, was one of the main economic hubs of early modern Europe which had long-established trade links with England, and offered many economic possibilities. Lisbon also offered another precious advantage as a Catholic refugee. Iberia was not troubled by the religious wars afflicting the Low Countries and France, which had been the initial destination for the first waves of English recusants. It was precisely the relative safety of Lisbon that led a group of English Bridgettine nuns to settle in the city in 1594, after a peripatetic existence between England, Flanders and France.

The arrival of the wandering English nuns was a propaganda coup for Spain, a clear demonstration of Philip II’s role as the leader of the Catholic world. However, the English Bridgettine became a serious problem for the Portuguese ecclesiastical authorities. Regarded as the last survivors of the English religious order, the nuns developed a particular institutional and national identity. During the exile in Spanish Flanders, the English Bridgettine sought to segregate themselves from their foreign sisters and to recruit only English women. These isolationist practices troubled the archbishop of Lisbon, who refused to grant such privileges, considering that they violated the rules of the Bridgettine Order and the decrees of the Council of Trent. The dispute would only be solved after the intervention of Pope Clement VIII, who decided to place the English nuns under papal protection, ensuring that they would always be allowed to only recruit their countrywomen.

The efforts made by the English Bridgettine nuns to preserve a distinct English identity was something shared by other Catholic refugees. The increasing association between Protestantism and Englishness made the identity of Catholic exiles extremely complex. In the eyes of many English Protestants, the fact that some recusants decided to leave England, and embrace the life of and exile under the protection of foreign rulers, made their Englishness and actions particularly suspicious. Such accusations led some exiles, like the Bridgettine nuns, to develop a sense of Englishness based on an ostentatious rejection of the cultural practices of their host societies, an attitude that, as the reaction of the archbishop of Lisbon reveals, often clashed with the cultural inclusiveness of the early modern Catholic world. Others, however, sought to accommodate their English identity with foreign cultural currents and modes of sociability. Students of the English colleges of Rome and Valladolid, for example, often used Italian and Spanish as their preferred idioms.

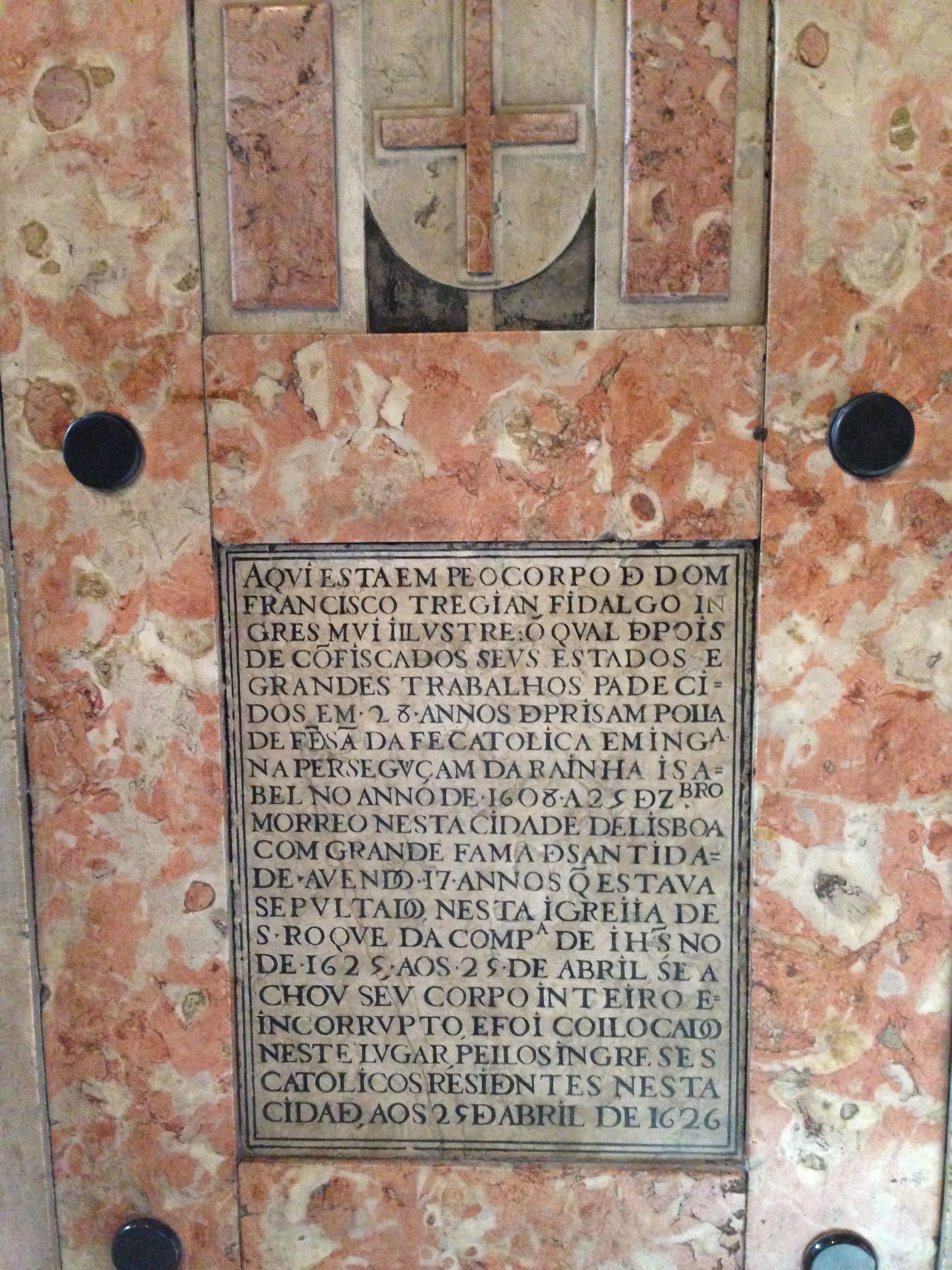

When Francis Tregian’s tomb was exhumed in 1625, the local English Catholic community sensed a rare opportunity to solve the tension between their national identity and Catholic universalism. Tregian’s body was found to be uncorrupted, confirming the odour of sanctity that surrounded his death. The news of the uncorrupted body attracted many Lisbonians to Saint Roch’s Church and rumours of miracles associated to the English recusant started to circulate across the city. Aware that Tregian could generate a popular cult and had the potential to be canonised, the English exiles staged a solemn ceremony to rebury the body. Attended by many locals, the ceremony celebrated Tregian as an English Catholic hero. The body was buried standing up (an allegory to his resistance to Elizabethan repression) in a new elegant, but discrete tomb in the west pulpit. While the epigraph was in Portuguese, the text celebrated the heroic and moral virtues of an Englishman who resisted against Protestant heresy. This option allowed the English Catholics of Lisbon to accommodate their Englishness to the host society, as well distinguish themselves from their Protestant countrymen who also lived in the city. In other words, Tregian’s tomb was creatively used as a symbol of Catholic Englishness which allowed exiled recusants to state their national identity and be a part of their host society.

João Vicente Melo