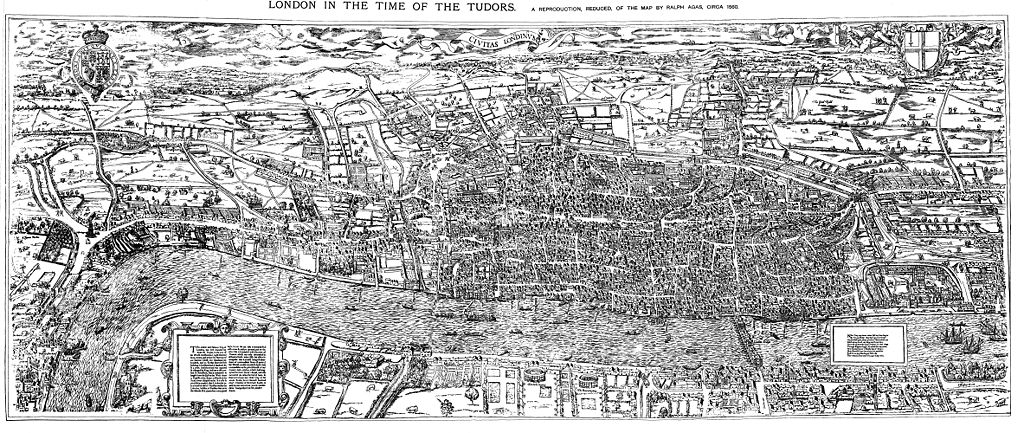

1st May 2017 marks the five hundredth anniversary of the first documented race riot and greatest outbreak of violence against immigrants in early modern London. Its story is one of anxiety and frustration that was directed as much at the state as it was at the foreigners themselves. In our own climate of fear and insecurity, its themes seem strikingly familiar, but it also inspired one of the most impassioned pleas for the protection of refugees in the English language.

Fights among drunk young apprentices was common enough on the May Day holiday in London, but in the days leading up to the end of April, 1517, there were whispers on the streets about bigger trouble brewing. Following a tough winter and a severe outbreak of the dreaded sweating sickness, there was a rising sense of discontent among the ordinary people, and foreign merchants and workers became popular targets of that frustration.

Edward Hall (1497-1547) was a twenty-year-old student at King’s College, Cambridge, at the time. The report he would write subsequently in his Chronicle is inflected by his mistrust of foreigners and his bias against the Lord Chancellor, Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, but it gives us the clearest account of the events. According to Hall, things had been set in motion over two weeks earlier by a disgruntled broker called John Lincoln, who blamed the foreign merchants and workers in London for everything that was arguably wrong with the city. He tried to get Henry Standish, the preacher appointed to deliver the hugely popular Easter Monday sermon at St. Mary Spitall in Bishopsgate, to drum up popular support for his cause. When Standish turned him down, he approached the designated preacher for the Tuesday, a Dr Bell or Beale. On the day, Bell began his sermon with a ‘pitifull bill’ about the ‘extreme povertie’ of the king’s subjects. The ‘aliens and strangers eate the bread from the poore fatherless children, and take the living from all the [artisans], and the entercourse [business] from all the merchants’, he claimed, and the only solution was a public uprising: ‘as the hurt and damage grieveth all men, so muste all men set to their willing power for remedy, and not to suffer the said aliens so highly in their wealth’. After all, God gave this land to Englishmen, ‘and as birds would defend their nest, so ought Englishmen to cherish and defend themselves, and to hurt and grieve aliens for the common weale’.

Small acts of violence started soon after, till on 28 April, a small group of young Englishmen were arrested for assaulting ‘Aliens as they passed by the streets’. That triggered what Hall describes as a ‘common secret rumour’ about a planned insurrection on May Day, when the city would ‘rebel and slay all Aliens’. Foreigners in London were obviously anxious. Hall mentions that many of them ‘fled out of the city’ as a precaution, and the Venetian Ambassador, Sebastian Giustinian later wrote back in his report to the Venetian Signory that he ‘represented this state of things to the Cardinal [Wolsey], who promised to make provision against any accident on that day’, but Wolsey and the Tudor establishment showed no actual signs of responding to the threat.

What happened next on 30 April 1517, the day before the riot, shows every sign of an administrative fiasco, in which a last-minute scramble to put safeguards in place to ensure civic safety ended up instigating the very thing it wanted to avoid. That morning, frustrated that despite his reassurances, Wolsey showed no signs of taking the threats seriously, Giustinian the Venetian ambassador decided to take matters in his own hands. His report to the Signory notes that ‘being warned of many threats used by the populace, and having witnessed many acts of violence perpetrated by them, [he] went to Richmond, where the King was residing, and showed him the peril to which all foreigners were exposed.’ Henry’s response was to assure Giustinian that he would ‘take every precaution’, although all he did was to spread the news that he was going to return to London with a large army to impose peace, ‘though in reality he never quitted Richmond’. Giustinian’s audience with the king, however, obviously got Wolsey to act: he summoned the mayor of London and the city council, and demanded if they knew anything about the rumours of the planned riot. ‘”No surely,” said the Mayor,’ according to Edward Hall’s account, ‘and I trust so to govern them that the king’s peace shall be observed.’ Then he hurried back to find out whether city officials were aware of the rumour. By this time it was 4 o’clock in the afternoon. By 7 o’clock in the evening, the Mayor and the city officials had panicked enough to hold an emergency meeting in the Guild Hall to decide on the measures to be taken. After much debate, they decided that the two options were to either impose a curfew or organise a ‘set of honest persons [and] householders’ to patrol the streets, and a message was sent to Wolsey just before 8 o’clock in the evening for his order. Half an hour later, Sir Thomas More, then undersheriff of London and Richard Brooke, Sergeant at Law, arrived with Wolsey’s decision, that a curfew would be imposed till 7 o’clock the next morning.

With the drinking and the festivities on the eve of the holiday already in full flow on the streets of the city, the aldermen of London now had barely half an hour to impose that curfew and get everyone back in their houses. One of the aldermen to rush back to their wards was Sir John Monday [or Munday], who saw two young men indulging in a bit of impromptu fencing or ‘playing at bucklers’ while surrounded by a large group of spectators. He asked them to leave, and when one of them irreverently asked why, he made the mistake of trying to drag him away physically by his arm. That small spark was enough: the standard rallying cry of apprentices, ‘Prentices and clubs,’ immediately started up around them. Munday managed to escape with his life, but the damage was done; the riot had begun. By 11 o’clock at night there were about seven hundred angry Londoners in Cheapside, from ‘serving men and water men [to] courtiers’, and within a short space of time their number had more than doubled to over a thousand. The mob stormed Newgate prison and took out the men who had been put under arrest on 28 April for attacking foreigners.

At Saint Martin’s, where a large number of mostly Dutch and French artisans lived, Sir Thomas More, in his capacity as the under-sheriff of London, almost persuaded the rioters to stop. However, in a moment of dramatic misunderstanding, some of the bricks and hot water that the besieged householders of Saint Martin’s had started throwing out on the mob struck a sergeant of arms called Nicholas Downes who was standing with More. His angry response, crying ‘Down with them’ in pain, was picked up immediately by the mob, and the riot continued.

At Leadenhall, they attacked the house of John Meautys, a merchant from Picardy and a secretary to King Henry VIII, who was suspected of harbouring French pickpockets and unlicensed foreign wool-workers. According to a report in the chronicle of the Grey Friars of London, Meautys barely managed to escape with his life by apparently hiding in the gutters of his house, but his house was looted. In Blanchappleton near Aldgate, the mob looted the houses of foreign shoemakers, and threw their stock into the streets. Although no deaths were reported, hundreds were injured – both foreigners and well-meaning Londoners who tried to pacify the rioters – and a swathe of destruction and unrest continued to spread across the city for over four hours. Worried about things going completely out of control, the Lieutenant of the Tower of London, Sir Richard Cholmeley, ordered his men to fire ordnance into the City, but ultimately the riot ran out of steam naturally. By 3 o’clock on May Day morning, peace had been restored in London. Now it was time for both the city and the Tudor establishment to pick up the pieces.

Nandini Das

[To be continued…]