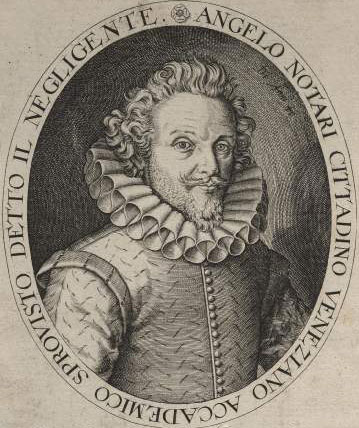

At the start of my doctoral research last year in the Archivio di Stato di Venezia, I spotted a familiar but unexpected name in the Venetian state papers. It was signed at the bottom of a receipt, in handwriting that I had only seen in a British Library music manuscript [1]. This was the signature of Angelo Notari (1566-1663), a Paduan singer, lutenist, and composer who immigrated to England circa 1610 and worked as a Stuart court musician. Early music specialists have recognized him for introducing a great deal of Italian music into 17th-century England, from virtuosic violin sonatas to theorbo-accompanied monody and madrigals. So what was his name doing here, amid streams of cipher in secret diplomatic dispatches?

Closer examination of these documents revealed that between 1616 and 1619 Notari was an informant for the State Inquisitors of Venice, a powerful counterintelligence division of the Republic’s centralized secret service [2]. This information has heretofore escaped the attention of musicologists, perhaps because Notari’s name is spelled differently in most Venetian sources, and political historians who have studied those sources never made the connection.

After the sudden death of Prince Henry Stuart in 1612, Notari temporarily lost his royal patronage and had to make a living elsewhere. He published his only known book of printed music [3]. He seems to have found employment at the Venetian embassy in London, only to be fired for bringing plague-infected items into the ambassador’s home. And then, like many of his musical contemporaries, he turned to espionage.

As an intelligencer, Notari was entangled in a contentious international trial involving the Venetian ambassador to England, Antonio Foscarini, and two of Foscarini’s embassy staffers. Notari approached various Venetian authorities in London with incriminating information about all three diplomatic agents, adding to an already long list of bizarre, yet serious accusations against them by other local residents. Notari’s detailed depositions accused Foscarini of disrespectful name-calling, indecent behavior during Mass, and more alarmingly, sexual assault. Notari also alleged that the embassy secretary, Giulio Muscorno, had slandered and publicly mocked Foscarini throughout the city. Notari eventually transitioned into paid work for the State Inquisitors. Thanks to Notari, they discovered that Foscarini’s valet, Ottavio Robbazzi, had been selling the ambassador’s letters to other foreign agents in London.

Foscarini, Muscorno, and Robbazzi were all discharged and imprisoned in Venice. While they awaited sentencing, Notari helped the State Inquisitors settle a debt that Muscorno still owed to an Englishman. This led to another international scandal when the English ambassador to Venice, Henry Wotton, tried to pocket the money for himself. After the trial ended, the State Inquisitors recommended Notari’s intelligence services to another Venetian official who remarked that Notari’s frequent presence in the homes of political elites made him an optimal candidate for the job. Several scholars have speculated that Notari became a spy for Spain by the early 1620s.

Notari aside, the Foscarini-Muscorno case takes several surprising twists and turns into musical territory. In fact, Muscorno’s own musical activities were of great significance to the trial. His musical talents gained him formidable allies at the English court who supported his aggressive campaign against Foscarini. And yet, the Venetian government ultimately held Muscorno’s music-making against him as evidence of criminal conduct; he was indicted for singing in Anglican churches and defaming Foscarini through crude, buffoonish musical performances.

As I continue my dissertation research on music and mobility, I’m thinking about music in this period as a major economic export and transnational currency, traded for more than just financial compensation. Music could buy valuable information and contacts. Foreign musicians in London capitalized on their art to gain entry into powerful political networks, thus rising to prominence in their own expatriate communities and indelibly changing the course of diplomatic history.

My journal article detailing Notari’s intelligence intrigues soon to be published in Early Music History. In the meantime, I’ll be sharing more on this subject at the annual American Musicological Society conference in Boston this November. Hope to see you there!

Alana MailesAlana Mailes is a PhD candidate in Historical Musicology at Harvard University. Her work explores issues of diaspora and migration in early modern music of Italy, Britain, and Ireland. She is also an enthusiastic performer of early music.

- 1. Angelo Notari, Add. MS 31440, British Library, London.

- 2. The Venetian State Papers in question are Inquisitori di Stato, Buste 155, 156, and 442. Some have been transcribed and translated in the Calendar of State Papers Relating to English Affairs in the Archives of Venice, Vols. 12-15, ed. Horatio F. Brown and Allen B. Hinds (London: The Stationery Office, 1905-9).

- 3. Notari, Prime musiche nuove (London: Engraved by William Hole, 1613).