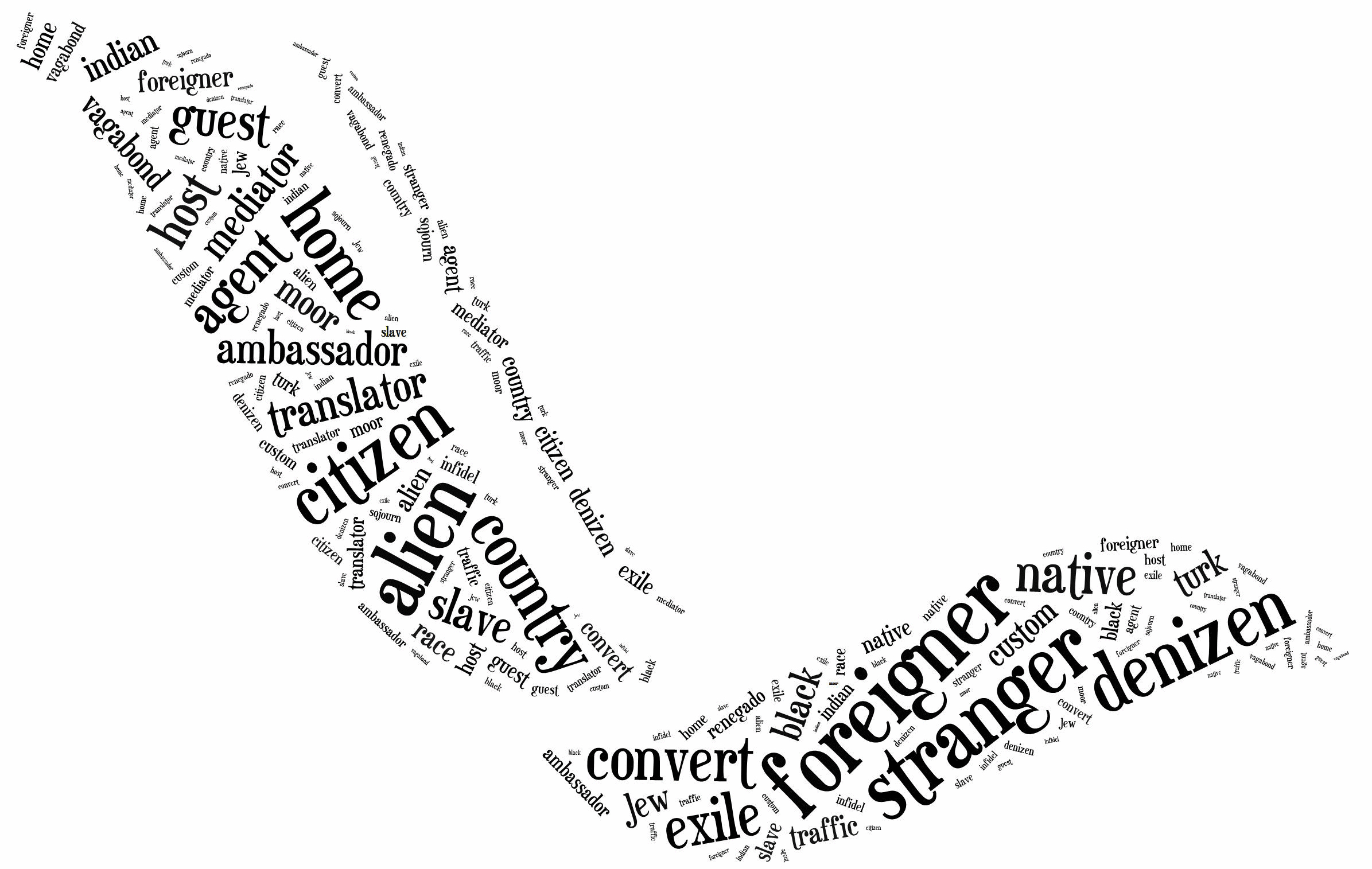

In Discourse touching the Office of Principal Secretary of Estate, Nicholas Faunt drew on his seventeen years of experience as Sir Francis Walsingham’s personal secretary to remark on the wide range of matters and tasks that secretaries dealt with. They were subjected to much ‘cumber and variableness’, he complained, that impeded an office that should be defined by a ‘special method and order’.[1] Like other bureaucratic figures with different titles but similar functions, secretaries acted as the overseers of early modern institutions and their complex administrative machineries, such as royal governments, merchant companies, universities, or religious bodies. The term originally derived from the Latin secretarius, a notary or scribe – individuals who served emperors and government officials and were often part of the apparatus of state expansion and imperial administration.[2] Most early modern treatises on secretaryship described secretaries as facilitators of communication and as cultivated servants who used their humanist education and mastery of rhetoric to guide their masters in their correspondence with others. Their function, as the Italian secretary Vincenzo Gramigna observed in Il segretario dialogo (1620), of the ‘pen-speaker’ (dicitor di penna) was to be ‘executor of the will of others’.[3] Thomas Dekker expressed a similar sense of the word when he wrote that the ‘Gunner of Gehanna’ (Satan), by ‘the Artillerie of his Secretaries penne, hath shaken the walls of his kingdome’.[4]

The production, analysis and management of information (letters, reports, and dispatches) was the secretary’s main task, whether for resident embassies and special missions abroad, or for individual employers in England.[5] As in the case of the ambassador or the envoy, the secretary was an oratore or a messenger, someone who mediated the communication between his master or prince and other actors. Expanding state and diplomatic interests relied on secretaries and clerks who played a pivotal role in overseeing the flow of intelligence produced and managed by various organizations. In the 1640s, the prophetic writer Lady Eleanor Davies appropriated this understanding of the function of the secretary as a trusted interpreter of sensitive information when she claimed a privileged access to divine wisdom, as ‘a Writer or Secretary, concerning the unsealing or interpreting this obscure piece to open the Vision of Daniel’.[6] That claim of proximity to the divine would allow Davies to overpass the restrictions imposed to the participation of women in the political and religious arenas, and to develop an active and interventive voice through her prophetic works.[7]

Although ‘at the pleasure and appointment of another to be commanded’, the secretary could enjoy a special status due to the sensitivity of the information to which he had access. The secretary was ‘a keeper or conserver of the secret unto him committed’.[8] Indeed, the term secretarius mentioned above related closely to secretum – the special chamber where confidential information could be written and stored, or a place of secrets.[9] Faunt’s work as a spy and intelligencer for Walsingham in Germany, France, and Northern Italy during the 1580s led him to emphasize the importance of ‘secrecy and faithfulness’ in managing business, but also in obtaining or discovering new secrets by conferring ‘with secret intelligencers both strangers and others’.[10] This link between secrecy and secretaryship allowed the secretary to enjoy a privileged, often intimate relationship with his master, one that the writer Angel Day believed was ‘more special than that between the son and the father’.[11]

The writer Robert Greene referred to that unique bond between secretaries and their masters in his popular prose romance, Mamilia (1583). While describing his protagonist Pharicles’ passion for Mamilia, Greene emphasized that as ‘his fire was the more, his flame was the greater, and not being able so well to rule his lust’, Pharicles had no option than to hide his feelings and ‘used himself for a secretary, with whom to participate his passions, knowing that it were a point of mere folly to trust a friend in love’.[12] While seemingly passive agents of their masters’ will, therefore, secretaries often played key roles in moments of mediation and interpretation. On the day-to-day level of bureaucratic service, the bond between secretary and master was not one of friendship so much as one of necessity, calculation, and trust, as John Higgins would note: ‘It spites my heart to hear when noblemen / Cannot disclose their secrets to their friend, / In safeguard sure, with paper, ink, and pen, / But first they must a secretary find, / To whom they shew the bottom of their mind: / And be he false or true, a blab or close, / To him they must their counsel needs disclose’[13] The access to sensitive documents on diplomatic, commercial, or political affairs allowed secretaries and other bureaucrats to use the information they produced and managed to their advantage. Many shared secrets with relevant or influential political actors in exchange for friendship, further information, or political and social benefits.[14] Through the intelligence networks they fostered, secretaries facilitated the growing market for news and information that connected men and women to the wider world.[15]As mediators between their employers and other polities, secretaries were often confronted with a series of issues that required a detailed knowledge of legal, administrative, financial, ecclesiastical, and mercantile affairs.[16] The multiple functions trusted to a secretary required an expertise and skills that were only possible through a privileged university education and humanist training. Treatises on secretaryship often depicted the secretary as a member of a restricted elite of scholars and bureaucrats recruited from universities and courtly milieus. For many graduates of Oxford, Cambridge, or the Inns of Court, secretaryship was often a stepping stone to prestigious posts in royal administration or diplomacy. In February 1609, the London gossip John Chamberlain wrote to Dudley Carleton that the poet John Donne, who sought professional advancement after the damage done by his secret marriage to Anne More in 1601, ‘seeks to be preferred to be secretarie of Virginia’.[17]

Those who did succeed in becoming secretaries tended to progress in the royal administration or obtain ambassadorial posts. Robert Devereux, second Earl of Essex, employed a young well-educated and well-travelled Henry Wotton in 1594, partly in recognition of the correspondence network that Wotton had cultivated during his ‘grand tour’ of the Continent.[18] Another example is Edward Barton, the secretary of William Harborne, the first English ambassador to the Ottoman court. In order to control the correspondence between the Sublime Porte (Istanbul) and London, Barton decided to learn Turkish and rapidly became a crucial negotiator in Anglo-Ottoman relations. As he became aware of the subtleties of Ottoman bureaucracy and letter-writing, Barton was able to advise Elizabeth I and her state secretaries to change the style, format and rhetoric of their letters to guarantee a favorable reception from the sultan. His ability to speak Turkish made him a respected figure at the Ottoman court, granting him access to various courtly factions and sectors of the local administrative machinery. Responsible for securing a steady flow of communication between London and Istanbul, Barton developed a complex cypher system which caused William Cecil, Lord Burghley to complain that the letters sent by the English embassy at Istanbul took too long to decipher. Barton’s linguistic skills and his ability to obtain and guard secrets were behind Elizabeth’s decision to appoint Barton as Harborne’s successor in 1583.[19]

In 1619, the MP John Pory, who had worked as an assistant to the geographical compiler Richard Hakluyt, arrived in Virginia to become secretary in Jamestown. Pory felt disoriented in this new territory, remarking on the ‘uncouthness of this place, compared with those partes of Christendome or Turkey where I had bene’.[20] Though ‘those of our nation and the Indians’ were suffering from ‘this Torride sommer’, Pory looked forward to stepping into the duties of his role: ‘I am, for faulte of a better, Secretary of Estate, the first that ever was chosen and appointed by Commission from the Counsell and Company in England’.[21] As secretary, Pory served as speaker in the General Assembly of 1619, the first English elected representative assembly to be held in America.

Throughout the period, the diplomatic sense of the secretary as a go-between continued to be used less formally to denote communication of other forms, from godly interpreters of Scripture to the heralds of heart-matters: ‘I must now impart’, confides the fraudulent Sir Petronel Flash in Eastward hoe (1605), ‘a loving secret…[and] you [shall] be the chosen Secretarie / Of my affections’.[22] While secretaries had the power to operate as agents of deception, as when an enamoured Lady in Mary Wroth’s Urania (1621) mistakenly treasured a sonnet though ‘the truth is his friend made it for him, and so was his Secretary justly’, the troubles of miscommunication nonetheless raises attention to the important, everyday role of the secretary in facilitating communication between individuals and across countries and polities.[23] Letters written by women to secretaries of state, and their personal employment of secretaries of their own, place women within networks of intelligence-gathering and the circulation of news.[24] The English aristocrat and Spanish courtier Doña Jane Dormer, for example, relied on her secretary, Henry Clifford, to maintain an active correspondence with other members of the Spanish nobility and English recusants and exiles scattered across Europe.[25] Lady Anne Clifford’s correspondence and activities as a ‘Maecenas’ (a reference to Emperor Augustus’ political advisor) and landowner often passed through her ‘chief officers’ and ‘secretaries’, George Sedgwick and Edward Hasell.[26]

Meanwhile, the cases of Barton in the Levant and Pory in North America demonstrate the importance of secretaries in the development of early modern diplomatic and state administrative systems, as well as their role in producing and circulating knowledge and in transmitting English systems and institutions in new territories. Their education, travels, and accumulated experience as intelligencers and often spies made them privileged go-betweens and experts with the capacity to shape the course of diplomatic exchanges.