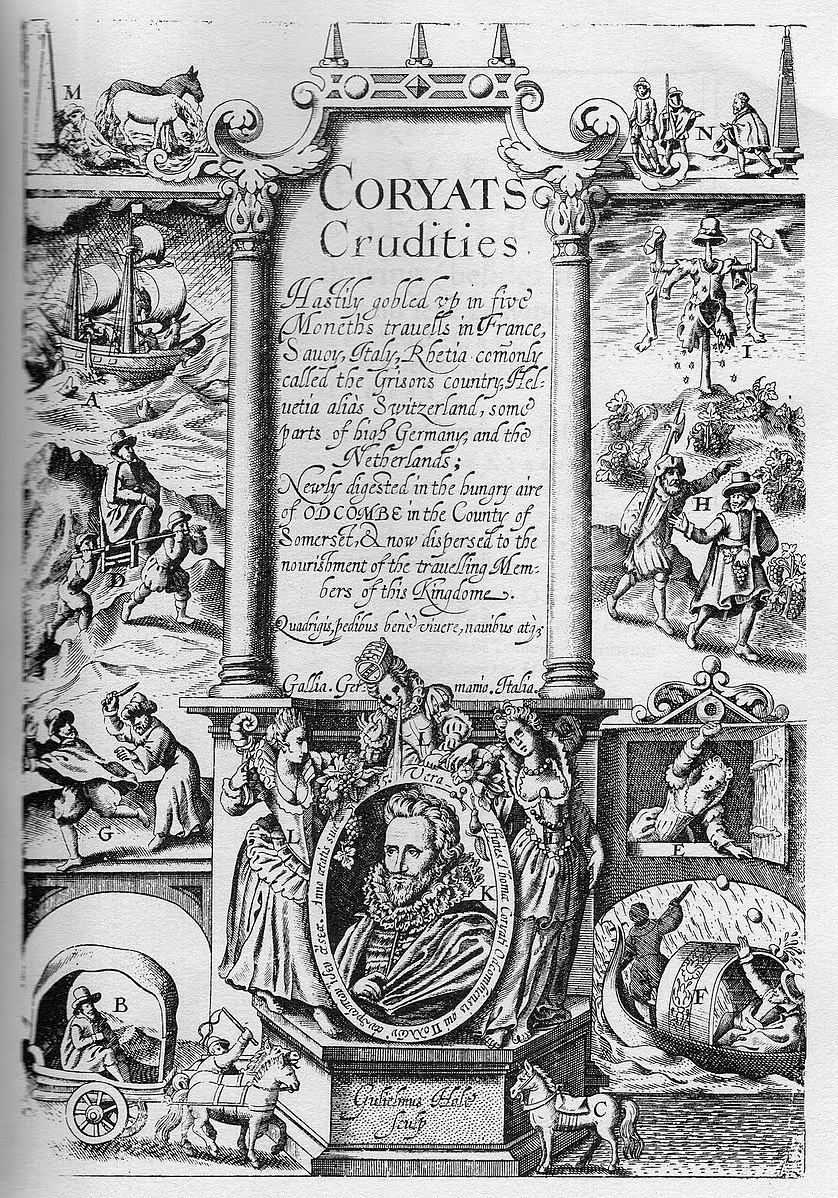

The etymology of ‘traveller’ is closely linked to the hardship of travelling, originating from the old French word travail and its associated verb, travailer. Both travail and travailer meant bodily or mental toil and exertion, and usage in the Middle Ages often linked them closely to childbirth, as well as to agricultural labour.[1] As one medieval author wrote, ‘Call the workmen and yield him here travail’, whilst the fourteenth-century poet William Langland spoke of ‘trewe travaillours and tilieres of þe erthe’.[2] By the fifteenth century, travail and the travailer were associated with journeying. While in France travailleur continued to be associated with toil and arduous journeys, in England, the term became interchangeable with the identity of the traveller. Mandeville’s Travels refers to a ‘way es comoun and wele ynogh knawen with all men þat usez travuaile,’ whilst Thomas Hoby, in his translation of The courtyer of Count Baldessar Castilio, would later write of Castiglione’s ‘yeeres travaile abrode’ as part of his civil education.[3] By the sixteenth century, the ‘traveller’ could be both a labourer and a journeyer. Thus on the one hand, a late sixteenth-century sermon could describe ‘the traveller’ as an individual who ‘passeth from towne unto towne, until he comes to his Inne’.[4] On the other, the geographer Richard Hakluyt could describe his labour of compiling the travel accounts in The Principal Navigations (1598) as an act of travel and travail, lamenting ‘what restlesse nights, what painefull dayes, what heat, what cold I have indured; how many long & chargeable journeys I have traveiled’ in the making of his compendium.[5] The conflation of toil and journey in the figure of the traveller was corroborated by biblical and classical tropes and exemplars. A 1597 devotional text drew connections between travel and banishment from heaven. The traveller who went ‘farre from his countrey and family, yet is desirous to returne thither againe’ was akin to humans ‘banished from this worlde’ and longing to ‘returne to heaven, our true borne country’.[6] In other texts, classical tropes of exile and homecoming of figures such as Ulysses and Aeneas took centre stage. The eccentric traveller Thomas Coryate warned his mother that his travels in India would not be done until he had travelled seven years, like Ulysses.[7]

It is important to note that not all travellers undertook their journeys voluntarily. In post-Reformation England, enforced mobility due to religious, economic, and political reasons could, and did, impose travel as a condition of survival on large numbers of the population. However, increasingly in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, the ‘traveller’ began to emerge as a figure undertaking largely voluntary travel in the hope of individual or collective profit and pleasure. The very act of going abroad made one a traveller. As Alison Games points out, ‘anyone who ventured out of England and Scotland for any purpose was a traveler in the parlance of the time’.[8] Commercial and territorial expansion involved the enlargement of a body of ‘professional expatriates’ who moved between cultures and nations, working as an arm of the English state, though often provoked by personal interests.[9] The Welsh courtier and poet Ludovic Lloyd commended Spanish expansion in this period, recognizing and envying the Spanish use of travel for commercial and territorial gain.[10] For Lloyd and many like him, the Spanish were successful conquerors because they were ‘greatest travellers’.[11] Over thirty years later, Thomas Palmer described the people of Britain, rather than the Spanish, as great travellers in their attempts to overcome geographic isolation. ‘The people of great Britaine’, being separated from the ‘maine Continent of the world,’ Palmer asserted, were ‘so much the more interessed to become Travaillers, by how much the necessitie of everie severall estate of men doth require that for their better advancement’.[12]

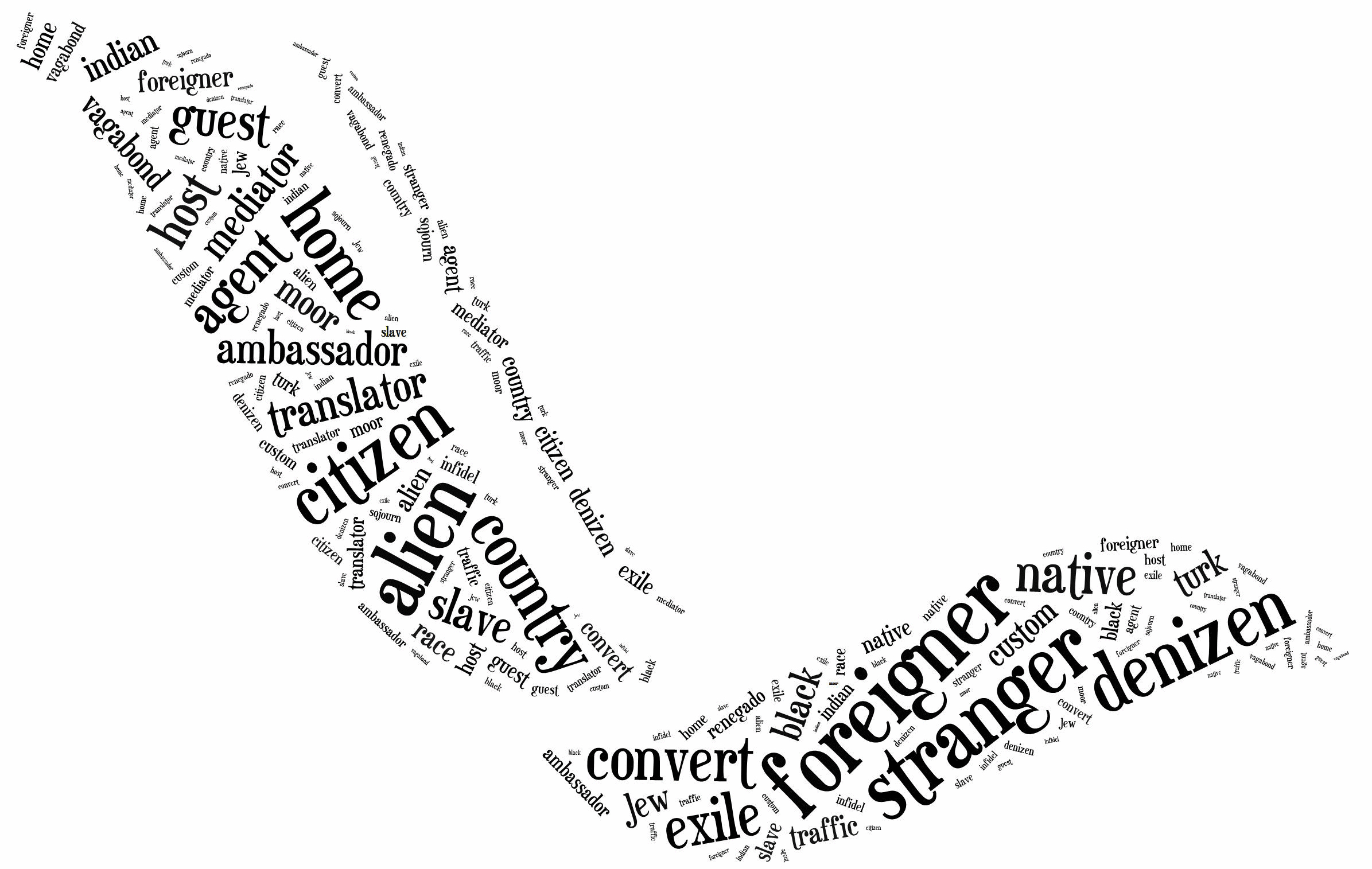

Throughout much of this period, the traveller emerged as a socio-political and economic agent of significance. Travellers could be both individuals seeking to experience foreign cultures and lands for personal benefit, or those employed to advance England’s goals as scholars, merchants, consuls, soldiers, sailors, chaplains and governors.[13] Policy-makers viewed travel as beneficial to gathering information and knowledge that served the interests of the commonwealth. The traveller informed and encouraged others to widen the nation’s perspectives and interests. Whether observing culture, language, history, flora, fauna, politics or law, ‘nothing should escape the careful attention and later recall of the thoughtful traveller’.[14] In 1576, explaining the reason for his journey to Geneva, Thomas Bodley admitted to being driven by the desire to gain ‘the knowledge of some speciall moderne tongues, and for the encrease of my experience…being wholly then addicted to employ my selfe…in the publique service of the State’.[15] Anthony Munday was a young apprentice to the printer John Allde in 1578, when ‘being very desirous to attaine to some understanding in the languages’ so that ‘in time to come: [he] might reap therby some commoditie’, he cancelled his indentures and embarked on a journey through France and Rome, subsequently using that experience as the basis of his work both as an informer and a writer.[16] As these two examples show, early modern travellers were often torn between the expectations of their role for the state and their own private interests. Munday’s career demonstrates how travellers were often in constant negotiation with their surroundings, and, by extension, with larger issues of political loyalties, confessional alliances and cultural difference.[17] They were driven by the possibilities of professional and social advancement as well as constant fear of religious, cultural and political corruption.

A wide range of travel advice literature available in the period placed considerable emphasis on specifying the desirable qualities of a good traveller. Jerome Turler’s De peregrinatione (1574), translated a year later into English, listed the people and groups that he considered unfit to be travellers. These included ‘Infants, Aged persons, & such as have weake bodies’, including women and ‘frantique and furious Persons’, all of whom were ‘unméet for [travel], not being able to abide those paynes that accustomablye befal the traveiller’.[18] Thomas Palmer outlined the professional and social qualities perceived as necessary for a perfect traveller. His meticulous strictures on the appropriate age, profession, and social background for the traveller were linked intrinsically to the expectations of travel and the traveller’s growing importance as a source of knowledge and information. His emphasis on the traveller’s duty to ‘make prudent observation of things beneficiall to the State’ is representative of a whole body of literature, the ars apodemica or methodus apodemica.[19] A benefit to the state, travel was encouraged by some who saw it as the duty of English subjects to spend time observing and recording what they saw for the benefit of the state and their personal advancement. A traveller himself, the lawyer Francis Bacon noted the potential impact of travel in his essay on the subject, urging his readers to ‘prick in some Flowers, of that he hath Learned abroad, into the Customes of his owne Country’.[20] In his account of his time in India, the chaplain Edward Terry wrote that ‘he is the best observer, who strictly and impartially so looks about him, that he may see through himself. That as the Beams of the Sun put forth their vertue, and do good by their reflection: so, in this case the onely way for a man to receive good, is by reflecting things upon himself’.[21]

However, such ‘reflection’ could also be treated with suspicion and unease. The mistrust of travel did not arise from an attempt to curb travel altogether; it was precisely because English authorities, and humanist thought, pitched the ‘traveller’ as politically useful that the figure of the ‘traveller’ became so contentious. Anxieties over cross-cultural encounter were frequently expressed, where fears of an individual’s mutability and abandonment of English values contained the possibilities of undermining the strength and cohesion of the Protestant state and Church. A traveller’s exposure to other religions and societies, for example Catholic Italy or the Islamic Ottoman Empire, were perceived as a threat to the national, spiritual, and physical identity of the individual traveller, even as knowledge-gathering abroad could lead to the stability or advancement of English interests. As Andrew Hadfield points out, the traveller who expressed overt enthusiasm about another nation, government, faith or culture ‘ran the risk of treasonably denigrating their own country’.[22] Like rogues and vagrants, English authorities were wary of the traveller’s loyalties, questioning their ability to ‘transform themselves into strangers’ fealty when they returned.[23] The substantial body of anti-travel literature produced in the period includes Roger Ascham’s Scholemaster (1570), which famously described the ‘English man Italianated’ as one who, ‘by living, and travelling in Italie, bringeth home into England out of Italie, the Religion, the learning, the policie, the experience, the maners of Italie’.[24] Yet despite Ascham’s apparent anti-travel rhetoric, he had himself travelled to Germany and Italy, describing his attempts to learn the language as leading him to being ‘almost an Italian myself’.[25] The Calvinist theologian Thomas Holland, who had spent time in the Netherlands, wrote of the pernicious effects of travelling into Catholic nations in particular. While Holland notes that ‘the wise and godly may suck sweetnes out of travail’, he also describes the ‘great abuses by travaile, and by it many corruptions have crept into florishing nations’.[26] Holland blamed ‘unprofitable, daungerous, and foolish travellers’ who ‘come to gaze, & to bee gazed on’ rather than travel to learn.[27] Another vehement critic of travel was the Norfolk bishop Joseph Hall, who lamented ‘how few young travellers have brought home, sound and strong, and (in a word) English bodies’.[28] Popular culture replicated such critiques. In The English Ape, the Italian Imitation, the Foote-steppes of Fraunce (1588), William Rankins described the destructive potential of the ‘merchandize’ gathered by the English traveller: ‘Thus (imitating the Ape) the Englishman killeth his owne with culling…He lovingly bringeth his merchandize into his native Country, and there storeth with instruction the false affectors of this tedious trash’.[29] In Thomas Nashe’s prose fiction, The unfortunate traveller (1594), the apish English traveller becomes a figure of ridicule, observed curiously by locals. ‘At my first coming to Rome,’ Nashe’s page-boy hero, Jack Wilton reports, ‘I, being a youth of the English cut…imitated four or five sundry nations in my attire at once, which no sooner was noted, but I had all the boys of the city in a swarm wondering about me’.[30] For many commentators, foreign travel and the adoption of certain positive customs at home was no bad thing, while most believed that unfettered interaction and ‘aping’ of foreign examples could lead to the loss of an individual’s national and cultural identity.

The growing numbers of English travellers going abroad was an increasing concern for English officials who sought to regulate such movement through stricter monitoring processes, such as the granting of passports and licences. These were granted by the Crown to signify that an individual had permission to travel abroad. In 1599, Lord Willoughby reported that another noble, Lord Hume, was ‘disposing of himself to travell’ and had requested that Queen Elizabeth grant him a ‘passport, and transportance as are needfull to a traveller’.[31] With the exception of established merchants, individuals were required by law to request for permission to leave the country, under the condition that they ‘do not haunte or resorte unto the territories or dominions of any foreign prince or potentate not being with us in league or amitie’.[32] This included passports for female travellers, as when Mary I’s lady-in-waiting, Jane Dormer, the Duchess of Feria, travelled with her Spanish husband the Duke of Feria to Madrid, via the Low Countries.[33] These passports not only shed light on individual travellers but on their retinues and wealth: Dormer travelled with six gentlewomen, a laundress, a yeoman of the wardrove, five gentlemen, two pages, two chaplains, sevel ‘gentlemen’s men’, a large number of horses and mules, silver, jewels, and dogs.[34] In addition, Dormer acquired a passport for her mother, her mother’s own servants and chaplains, and other attendants and money.[35] As such licences show, passports were designed to protect the individual and to the state, seeking to monitor the circulation of people and goods into foreign spaces and to curb a traveller’s spontaneous decision to visit places not designated in their passport.

Although the Tudor administration sought to exert greater control over those who crossed its boundaries, the attempts to regulate the movement of travellers was only so effective. Once abroad, travellers could ignore the parameters of the licence, choosing to travel where they wished, and at times for longer amounts of time than such licenses allowed. Edward, Lord Zouch described his passport as nothing less than ‘an imprisonment’, complaining that he could not ‘tell whether I shall do well or not to touch the part of the licence which prohibited me in general to travel to some countries’.[36] In the 1570s, Edward de Vere, seventeenth earl of Oxford, went to the Low Countries without a licence, then on to Italy. Despite attempts by William Cecil, the earl’s father-in-law and secretary of state, to call him back, de Vere refused to return.[37] Some years later, James I himself acknowledged the difficulty of enforcing the licenses abroad, noting how travellers ‘under pretence of travel for their experience, do pass the Alps...[and] daily flock to Rome, out of vanity and curiosity to see the Antiquities of that City; where falling into the company of Priests and Jesuits’.[38] As James alluded to, the root cause behind spiritual warfare and fears of political degeneration was often the potency of wonder and the issue of return. The beguiling alternatives to English life that travellers encountered abroad always carried the possibility of rendering the traveller ‘averse to Religion and ill-affected to Our State and Government’.[39] Cross-cultural encounters thus risked splitting the loyalties of an individual. This concern became increasingly problematic as travellers became colonists and settlers, the chief instruments in English expansion. This sense of separation or distance is evident in letters and poems between friends. ‘Went you to conquer? And have you so much lost / Yourself?’ John Donne writes in a poem to his friend Henry Wotton, then in Ireland.[40]

The imaginative possibilities and the practical world of travel are both evident in much writing of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, from travel narratives to advice books to language manuals. The rise of print and literacy made it possible for one to travel from the safety of their own chambers, or the playhouse, with reading about other places and peoples becoming a means of experiencing the world’s diversity. Many women were travellers on some scale, moving by coach, ship, or horseback to new households as a result of marriage or as the wives of governors and diplomats.[41] Aletheia Howard, Countess of Arundel, travelled to Italy several times in the 1610s and 1620s, once with her husband and another time without him, absorbing Italian culture, collecting books, and sitting for portraits.[42] Whether on royal progress from Edinburgh to London or on a ship crossing the Indian Ocean, the traveller fought the perils of disease, corruption, and death to experience the unfamiliar, satisfy curiosity, or out of political or spiritual devotion. At the same time, travel tended to be viewed as a temporary activity. Like Odysseus’ trajectory, the ultimate aim was to return; but home did not always look the same after being elsewhere.